|

It’s upsetting to see the level of hypocrisy and invective regarding the black airman who was shot by the police for answering the door with a gun in his hand. So many people I formerly respected went from zero to “fuck the police” over a single video without any debate or analysis of it. Those who have attempted to inject nuance into the rhetoric have been digitally lynched.

I’m really disappointed by a lot of people I otherwise agree with. This incident among others has illustrated a few things. Yes, people have always hated the concept of police because no one likes being told what do to by someone with the ability to back it up by force. There’s always been a segment of the freedom/veteran/gun/prepper/whatever community that has had a “fuck the police” attitude but in this case more than any others it sounds purely like a bunch of ghetto blacks upset because their criminal son got shot. The conflation of “any killing that looks questionable to me is murder” also bothers me. Manslaughter, sure. A civil tort, sure. Wanting to have a discussion about tactics, stress inoculation, etc. that’s one thing, instead it has become personal. Well, frankly fuck you for being stupid. And that’s it. The ignorance, the allowing oneself to be drug around the nose by emotion, and the refusal to look any further than those bare emotions is what bothers me. Events like these are why I believe propaganda is so powerful. The a large number of people, may be even a majority of people, are fundamentally unable to separate emotion from fact. Nor can they separate their personal feelings and fears from what are ultimately events totally unconnected with them. I do believe that the state of the world is a fractious one and the pomposity we’re seeing here is a symptom of how people are feeling. Ultimately, I think they think “That could be me!” for one reason or another. Statistically speaking, it’s unlikely, but this is the crowd that has been demonized by the government for the past four years. We all are stressed about money, the security of the nation, our politicians that ignore use, the blatant one-sided criminal persecution, and the perversion of the justice system. So why shouldn’t a right-leaning citizen be suspicious of the government? In the end, the aggrieved citizen lashes out the nearest target. For most, the only negative contact they’ll have with law enforcement is local police. Thus, it’s the street cop that gets the animus that is probably better directed at the President, Congress, the FBI, etc. Psychologists will tell you that anger and lashing out often correlates with a sense of powerlessness. The feeling of powerlessness obviously derives from being marginalized and demonized by the political-economic situation today. People are upset and afraid, so they make snap emotional judgements and refuse to look at more nuanced approaches. So to conclude, I think this incident has become an online way to vent frustration and powerlessness. That is understandable, but to see a crowd that has reasoned out so many other things, has overall correct opinions, only take a purely emotional path and broadly paint an entire system is sad to see. So what is the lesson here? Never, ever comment or get involved in police stuff on Twitter. Just ain’t worth the aggravation. And that’s where I’ll leave this piece, with a tone of decency. Yes, that Cresson H. Kearny, from Nuclear War Survival Skills. From his Jungle Snafus ... and Remedies. Within two days after Pearl Harbor, the headlights of all U.S. Army vehicles in the Canal Zone and Panama were painted opaque black except for a horizontal translucent red stripe painted across each lens. The leading protester against red blackout lights was a reserve officer, an experienced railroad man. He knew that red lights are used to warn of danger because a red light can be seen farther away than an equal-candlepower light of any other color. or white.

The first Jungle Platoon had found that small flashlights with blue cellophane film over their lenses provided enough light even on the blackest nights to enable men to cut nails. And especially in jungle a blue light, similar to the bluish lights given off by rotting wood and some tropical insects, attracts much less attention than a red light. To help eliminate red headlights, I presented pertinent facts to the three officers charged with resolving the blackout headlights controversy. They had not realized that the daytime sky looks blue because the blue wavelength component of sunlight is scattered the most by molecules and particles in the air and that red light, having the longest wavelength in the visible spectrum, is scattered least and can be seen farthest away. Within a few days the red stripes had been scraped off the headlights of Army vehicles in Panama and replaced with translucent, thin, light blue paint. Lightweight blackout flashlights with blue lenses were issued to many of our jungle troops during World War II, beginning several months after Pearl Harbor. They had a small bulb and a single D cell, good for many hours. In The Marauders, Charlton Ogburn Jr's classic on the climax of the Burma campaigns, on page 172 I was pleased to read, "We were careful to display the blue gleam of a blackout flashlight...." Yet by the time Americans had begun fighting in Vietnam, many military flashlights were provided with red lenses, and none with blue. The enemy can see a red light much farther away than a blue one of equal candlepower. Today blue blackout flashlights are long forgotten. Now some of our jungle troops can use a book-sized receiver to look up at a Global Positioning Satellite and immediately team within a few meters where they are on a map. A red light seldom will be needed to read maps while preventing temporary loss of good night vision. Except for a few leaders. American jungle soldiers will need only blue-light flashlights. With blue lights they can move at night without as much risk of getting shot as when using flashlights emit-ting a more easily seen red or white light. Furthermore, at night a jungle soldier with a small blue-light flashlight shielded by his poncho usually can safely doctor his cuts and scratches and remove ticks and thorns. Many American jungle fighting men were thus enabled to help themselves keep healthy during World War II. Unfortunately, our Services' concentration on getting ready to fight the Russians in Europe or the Middle East led to the elimination of blue-light flashlights and most other combat-proven jungle equipment.  Imagine if the October 7, 2023, Hamas attack on Israel happened in the United States, not in one city, but dozens. And on top of that, the plot was calculated to be as devious as possible, leveraged to hurt America where it was softest. Kurt Schlichter’s The Attack is just that; nearly everything we feared post-9/11 but writ far larger, enabled by our callous and feckless government that has left the border unchecked. There’s a lot to unpack, but I’m only going to cover the high points. Frankly, it took me a while to finish the book and consolidate my thoughts on it. When you live in a world like I do, researching this stuff and having a job that involves bad things happening to people, you get sensitive about reading fiction. So my apologies to Kurt for not wrapping it up sooner. All while reading the book, I felt a sense of rage. The carnage in the story is appropriately outrageous but also the ability to generate strong emotions is a sign that the author did a good job. More than this, my emotions came with the understanding (and fear) that this is indeed plausible. Some disclaimers:

The book implies that casualties (both dead and wounded) were in the low hundreds of thousands, without creating a spoiler. Please note I’m taking the story by its spirit and am not offering criticism based on my very high bar of verisimilitude. It’s all plausible; I just think at a much smaller scale, but it’s done well enough that even my borderline autism can accept it. Now I say this part largely to the people who have no real conception of risk analysis, not to criticize the plot. I do not think mass terrorist attacks, with guns and bombs alone, are capable of creating hundreds of thousands of casualties. I know many of you watch Fox News and assume every brown person crossing the border is a terrorist, but that’s not the case. It’s hard to mobilize a legitimate army, let alone one of such size. The 2008 Mumbai terror attacks that were the first “at large” mass shooter style terrorist assault had a kill ratio of 10:1, but this was largely based on target selection that included a crowded railway station and two hotels. The October 7 Hamas attack, despite having approximately 3,000 terrorists to 1,143 victims killed, had a .38:1 ratio. A 10:1 ratio would require over 10,000 attackers. While that number comes across the border in just a few hours, I seriously doubt that many can keep their mouths shut. We’re taking about people who are less-well disciplined than a buck private drunk at a strip club who’s about to deploy. Heck, Al Qaeda tried to get 20 people in to attack the US and only managed to get 19, plus a few other losers who were rounded up after-the-fact. So no, at this scale I can’t see it happening, so even with the millions flowing unchecked across our borders. It’s too hard to get enough people dedicated to that and keep their mouths shut. Plus, the USA is huge in both area and population, so that kind of per capita terror would be hard. I could see the magnitude of such an attack occurring in Great Britain, but not the United States. In the UK, the infiltration of Muslims across society is far greater than the US and in the former, the level of radicalization is much higher. Not that it can’t happen here, but for the same level of permeation it would take more time and great numbers of immigrants. With its head start and the British police unwilling to offend Muslims, plus the practical toleration of radicals in their midst, it is the perfect breeding ground for such an attack. Couple that with largely unarmed police and a disarmed populace and you have a recipe for widespread slaughter. In the US for real, we would probably see a number of attacks across major metro areas, say perhaps a dozen. They may even occur in smaller towns to create a perception of “nowhere” being safe. Kurt certainly carries that across in the book when residential areas are attacked. Again, I don’t think this would be part of anyone’s deliberate plan, but it is useful analogue to things that might happen. For instance, an October 7 cross-border couldn’t really happen in the US the way it did in Israel, but similar events could happen for different reasons. Like the neighborhood attack could be a looting horde of rioters and urban gang members or, in a more dystopian future, racist cartel gangs from Hispanic controlled cities. Or it could be warlords in a James Wesley Rawlesian SHTF collapse (which he did write about). The leftists joining the terrorists? Well the last week’s campus protests certainly opened my eyes to the possibility, although I don’t think such a thing would be pre-planned. Also most of these people are just idiots, not willing to go along with such slaughter for slaughter’s sake. Again, however using fiction as an allegory, what if these dumb kids converted to Islam? Instead of the leftist Weather Underground, they become soldiers of Allah? Or instead of being a Muslim attack on America, it’s a socialist revolutionary pogrom against Republicans or something? Such atrocities have happened in most, if not all, communist revolutions. There are some things I feel Kurt left out. I don’t blame him for some of it. A book can only be so long. Also, Kurt is a legitimate lawyer, officer, commentator, and author; he can’t go to all the dark places that an unaccountable self-published author can. Besides, that’s a good thing. Until now, I’ve always felt “safe” reading Kurt’s books. Kelly Turnbull always saves the day and even the nasty, uncomfortable things that make me as a reader squeamish are handled very softly. Yes, even I who professionally deals with mangled people and horrific stuff get a little soft when it comes to torture, abuse, tragedy, etc. Even though The Attack made me nervous, Kurt wasn’t gratuitous about any of it. Just enough darkness to communicate the emotion and message but also with enough heroism and revenge to rally the dampened spirit. And the part about the .45s? Heck yeah! We would TOTALLY do that. (That part is clearly drawn from how the Israelis responded to the 1972 Munich Olympic massacre). The calls for revenge would be absolutely nuts in the United States. Someone would have to be nuked in reality. Heck, even a president like Obama would probably do it just to avoid a scene out of the French Revolution. Kurt is subtle about it, but it’s clear that America plays by the Big Boy rules after this and is totally unapologetic, as we should be. Our respect with countries like China and Russia, if they had clean hands, would probably ironically go up. The infrastructure attacks are also entirely plausible. I figure in any World War conflict with Russia or China, our power plants, water systems, and communications grid will be hacked and destroyed. Kurt hits the nail on the head with this section and it’s been discussed widely, so we don’t need to go there too much. Just keep in mind that even a conventional war in the 2020s will bring American infrastructure to its knees. Ethnic violence against mosques and Muslims would be commonplace and unstoppable. The fury the American people would pour out would go beyond righteous retaliation to…dark places. Reprisals would be awful in the vein of the Christchurch, New Zealand, mosque shootings. Predominately Muslim communities like those in Michigan might even come under siege. Police would be too buy responding to the attack, dealing with the aftermath, or otherwise “non-mission capable. The main theme of The Attack is that police are utterly overwhelmed by the scale of the attacks. This is a fair possibility even in the real world due to the nature of police staffing and tactical responses. Smaller cities may take their entire scheduled force for the day to equip the equivalent of one military squad. 8-12 officers for a major city can be the police presence for an entire district/division of a city, meaning that reinforcements have to come from the next one. Then you need officers on perimeter, officers to evacuate the wounded, officers doing crowd control, etc. Also it’s not like a light goes on in these incidents where cops drop their procedures and act as soldiers might. Cops aren’t trained to handle these like spot fires; put one out and move on to the next. Christopher Dorner was one man who tied up LA law enforcement for a week, and when they cornered him, cops had to hold back other cops who wanted a piece of the action. Every cop from miles around will swarm to these scenes and not in an organized fashion. So yes, law enforcement would be rapidly overwhelmed. Most cops aren’t tactically minded nor do they have the mindset of soldiers. Plenty will be brave, but a lot more, even if they don’t chicken out, simply will not know how to respond appropriately. If their agency gave them active shooter training, it’s likely against one loser in a school or something, not a fire team of jihadis. The average beat cop will be ineffective. Look at how badly LAPD was pinned down by the North Hollywood bank robbers. This is where the militia system should fill the gap. If we were a serious country, American minutemen would be able to rapidly respond to the incidents as they cropped up. But we lack any mechanism to organize such a response and most men who have the willingness, and the equipment to, don’t have the training. I’m sure that plenty of veterans or gun-bros would step up and fill the gap, but not enough. We’ve already seen this happen to some extent. During the Mandalay Bay shooting in Las Vegas on October 1, 2017, police reported citizens were attempting to arm themselves from police cars (allegedly Dan Bilzerian) to fight back. When that ex-airman shot up a church in Texas, some dude in town grabbed his rifle and took the loser out. And let’s not forget United Flight 93 where the passengers probably beat to death one or two of the hijackers and almost took back the cockpit with hand-to-hand fighting. America has something that practically no other country, even Israel, has: a very well-armed populace. We have men who make tactical shooting and preparing for events just like this a hobby. Guys would come out of the woodwork to fight back. The shame of it is that our laws prevent the willing volunteers from being better armed and trained as a civilian auxiliary. Even so, anyone fighting back will disrupt the terrorism. Kurt touched on this somewhat but I feel that the scale of it was less than it would in reality but hey, you can’t cover everything. If police couldn’t control the situation, guys with ARs and plate carriers would enter the fray. I certainly would. Spontaneous self-organization response teams would form as would neighborhood defense groups. Long-term, private tactical response groups would form the way that adult softball leagues do. I gotta point out that the “just respond” attitude for particularly federal law enforcement was great thinking; don’t respond to your office or group, just go stop the killing nearest to you. In fact, this is the entire idea behind the militia concept. Citizen responders with military-grade firepower at home can handle the situation themselves without waiting for SWAT or the military to save them. How many lives would have been saved in Israel if their people had ARs and plate carriers at home? That’s the big take-home lesson from The Attack. At some level, in some places, America will one day soon have something like this occur. It is one of the inescapable lessons of history that barbarians will eventually come. As I’ve said in my own books, fiction can be a way to help us mentally prepare for “unthinkable” scenarios. The Attack should be seen that way by the reader. How would you react? How would you prepare? How will you feel when it or something like it does happen? Let the story tug at your emotions. Feel them. Consider you and your family being in that situation. Can you rise to the occasion? I’d like to think that the book would serve as a stern warning to our officials and authorities, but we all know government is deaf, dumb, and blind. You may also want to monitor Big Country Expat’s blog; he’s also going to do a review and I’m sure he will colorfully express things I wholeheartedly agree with, but in his customary “frank” style. Sometimes you just gotta be honest with how you feel and he’s got a great way of being blunt and true to the emotions. (He also went to an art school so he’s good at the literary criticism thing too). We actually didn't shoot, despite putting targets down range. Why? No cans, for one. Two, the idiots were actually so close we thought it would be rude to start shooting in the darkness. The morons would have probably been utterly terrified that we were shooting and they would have no idea we had everything under control while wearing NODs.

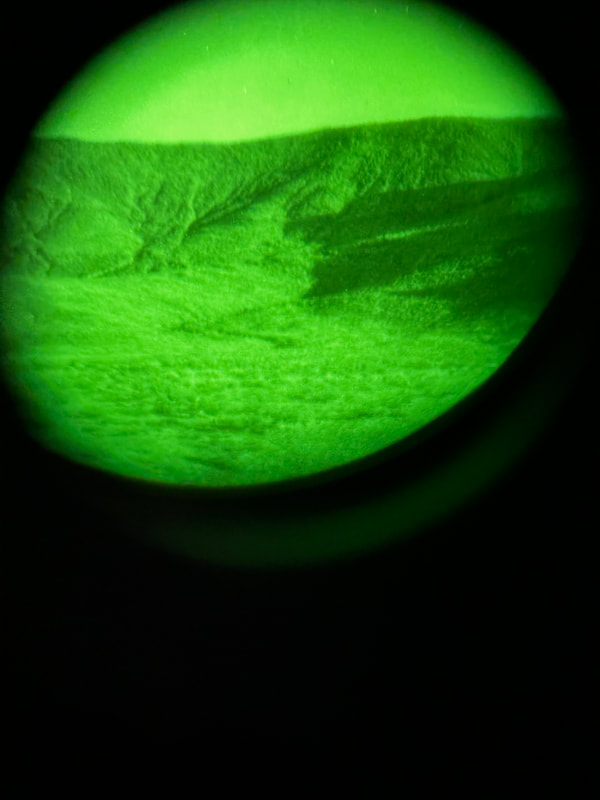

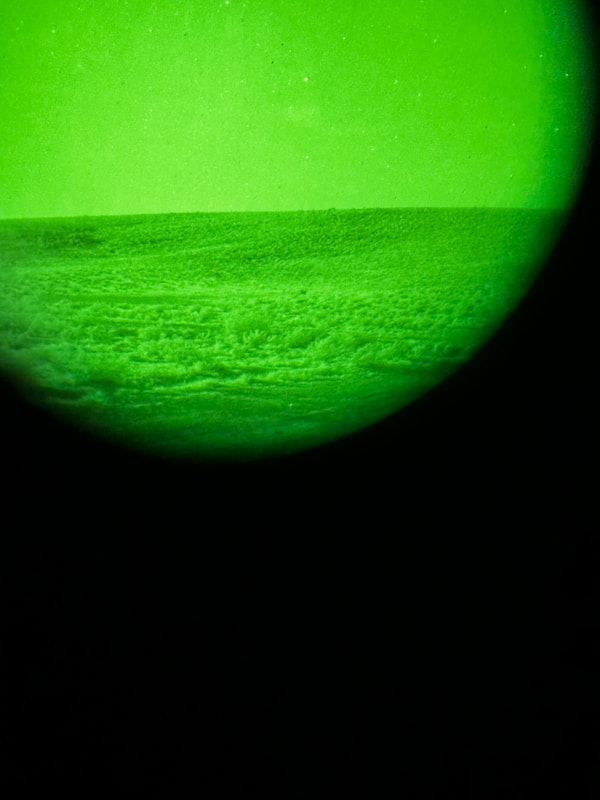

Second, we also had a thought that they might be homeless or at least boondockers, and while fucktards who camp at any time, night or day, on a BLM shooting area, don't deserve any courtesy, disturbing homeless car campers who aren't shitting up the city itself would be too inconsiderate of us. Third, they were outside the ricochet zone but they wouldn’t know that. Also, unlike during daylight shooting, there would be no way to see them and one of the dumbasses might be out in the moonlight without a cheap flashlight to mark their position. Might be bad. Finally, we were up-moon from them, meaning we were backlighted. If they felt threatened and were armed, they had a clear silhouette of us. Discretion being the better part of honor, we packed in the targets after we played around with the different settings without firing a shot. I established a rough converging zero on that Somogear fake PEQ-15 I picked up. I have some questions about the illuminator (IR laser flashlight) but need to try it on a moonless night. One thing we noticed that under the monocolor of NODs, a white painted steel target doesn't really stand out. The lasers will reflect off it though. So we went driving in the darkness on desert roads. Driving IS possible with a monocular like the PVS-14, but there are a couple of caveats. 1. We had a full moon. Great contrast and the shadows weren't really deep. 2. We left before astronomical twilight was over, meaning there was a lot of sky light available. If you have both eyes open and enough ambient light, your brain will fill in the image well enough to give you some depth perception. I had issues keeping it "between the lines" so to speak but otherwise did fine. Got up to 80 on some sketchy roads. Pretty sure hearing a truck blasting by a high speed in total darkness freaked out the 'tard campers. Also when driving at night you gotta cover up the instrument cluster and turn off the dash iPad, I mean the stereo screen. This isn't a Crown Vic or Tahoe where you can just hit the blackout button. The nice thing about being the driver and wearing NODs is, that unlike my limited professional experience with them looking for agricultural thieves, I can control the vehicle and didn't get seasick. With more practice a passenger shouldn't have this problem either, assuming the driver isn't a jackass or a bad driver. As far as my personal PVS-14, well you can see I need to get a better photography solution for it than holding an iPhone up to the eyepiece. The three camera system in the iPhone Pro sucks for this kind of thing. Also the halo (ring around bright lights) are why I suspect this otherwise flawless tube was kicked from the military line to the civilian side. NV tubes for civilians are the ones for the military that don’t make the grade for some reason or other; not quite “rejects” but that’s literally what the engineers call them. All ITT Pinnacle tubes of that era had a noticeable autogate whine but I’ll take that over a big, splotchy black blem any day. Lastly, I think I need a 2.26” riser for proper passive shooting through my red dot. The 1” riser didn’t cut it, and the 1.93” was a stretch. BUT the biggest issue was one of focus. NODs can’t really focus on everything like your eye. You can focus to infinity, put on the day cap for a pinhole effect, but neither will make the red dot and the target come right into focus. Again, I’m late to the passive shooting party so I need practice, but I’ve read that focus and aligning a monocular behind the red dot can be challenging so it’s not entirely me. No, active IR won’t get you killed; using it stupidly and without discipline will. But that’s for the book. 😉 Otherwise, it was pretty easy to get the rifle at least up and on target, especially with the laser. And yeah, that Somogear was WAY brighter than the Steiner COBL CQB laser I was using. I could see the dot but not as clearly and it too slightly more mental effort to recognize it. In full moonlight or ambient conditions, I’m going to have to pony up some money for a proper IR laser. Video taken of the valley through the PVS-14 itself using an iPhone. A link to the Twitter thread if you want more video. My Somogear “airsoft” clone PEQ-15 arrived. This is a Chinese replica multifunction aiming laser (MFAL) that retails for $250 and is touted as having laser output levels in excess of civilian-available laser modules. According to reviews and enthusiast testing, this device exceeds the federal guidelines for laser power, which is its major appeal.

Before we continue, I did not buy this for operational use. I have Steiner COBL that real use and an Aimpoint Pro Patrol on a Unity riser. Eventually I’ll buy a MAWL but I’m cheap. This is for testing and evaluation (T&E) purposes in a training environment. As for why specifically I got this when I already have one was to mess around with the laser illuminator. Note that devices like the PEQ-15 have a few features; visible and IR aiming laser pointers and an infrared illuminator. You need an IR spotlight to identify targets downrange the same way you would use a white light. My COBL doesn’t have an illuminator and my white/IR flashlight is not good at long range. Now rather than use LEDs and reflectors, proper MFALs use laser illuminators which are basically laser flashlights. A separate infrared laser (not the IR aiming laser) is designed in such a way that the beam is broader than the aiming beam, but still tighter than a flashlight beam. This gives you a powerful, narrow beam that is capable of lighting things up at long-ish range. The full power element comes in because, surprise, a more powerful laser will go a lot further than a neutered civilian one. The Somogear is billed as a “full power” or at least higher power that is not compliant with federal laser safety regulations like your civilian version PEQ-15, the ATPIAL-C, does. Apparently the Federal Laser Police have better things to do than bust imports of these things. Do you need a “full power” laser? Not really. You aren’t lasing targets for an A-10 but the aiming portion isn’t why I got it and not why you want full power. Again, I have my own laser that I can pick up at 500 yards, but to summarize, full power is about the laser illuminator, not the laser pointer. I do not endorse using Chineseum products, especially for operational purposes. If your life depends on it, buy American or at least European. Again, this is a training tool that I’m going to review, not something I’d trust my life on. Now if you can’t afford to drop another couple grand on a quality MFAL but you already have night vision, this isn’t a bad temporary halfway measure. However, understand that it may fail you when you need it. It should be replaced with a quality device as soon as possible. Reviews indicate that these things can have problems. Chinese quality control sucks and at this price point, it’s hit and miss. The electronics are supposedly “potted” to withstand rifle recoil, but some users report no issues after hundreds of rounds and others failures after only a few shots. The polymer case can crack (there is/was someone replacing them with aluminum housings). While they generally hold zero, the mechanism isn’t as robust in the real thing. Again, these were intended for airsoft and probably just beefed up a tiny little bit once the Chinese realized American gun owners would buy them. Field use will follow in later posts, but I want to summarize a couple things.

For what it is, it’s not bad. Clearly not a real PEQ-15, but it feels robust enough. The remote switch is crappy but whatever. You get a nice pouch with it. The following is the "sequel" to my novel The Dad With a Flamethrower. Sitting in the warm sun on this balmy Easter morning it was hard to imagine that six months ago I killed three burglars, winged a fourth, and set three guys on fire with my homemade flamethrower. The last three guys the law didn’t know about, officially. My wife and kids never returned to that house. No, they stayed with my brother as I expeditiously sold the house, paying a premium on the new one far, far away. Raylene and the girls were over at the HOA park playing on the swing set in the glorious spring sunshine as I sipped flat champagne. Since today was a day of thanks commemorating the resurrection of the Easter bunny, as our three year old Remy explained, it felt appropriate to express my appreciation for us being alive. And me not in jail. I couldn’t say that the world was perfect now, but my family was safe and our corner of the world—one far calmer than we lived in back during the election and Jack-o-Lantern season. So with a toast of my nearly empty glass, I said my thanks. Filed away in my study (and with my attorney) was a notice from the DA in our former county clearing me of any charges. That meant, under the laws of the state of Fremont, I got off scot-free. State law had been changed so that a self-defense shooting found to be just that inhibited any future prosecution. Because of a history of politically-motivated murder charges stemming from self-defense in the 2020 riots, the Legislature had deemed it necessary. In most states, even a completely righteous self-defense killing could be charged as murder and there was no statute of limitations on that. The flamethrower was a stickier thing, but the cops who responded to the looting gang that arrived on our cul-de-sac believed the fire was from a dropped Molotov cocktail. Of course, when the burn victims showed up at the hospital ranting about a guy with a flamethrower the charge nurse called the police. Not a single neighbor talked and my DIY human incinerator was long since torn apart and sent off to different landfills. Only the psychological scars remained. Now I was Ross Porter, gunfighter. Going into that disaster I never thought I would have been capable of doing what I did. I suppose that’s why we can’t see what tomorrow would bring; too few of us would have the courage to do what’s necessary. I was an entirely different man now. Still a little flabby (working on that), but definitely no longer The Guy Who Didn’t Get The Memo. A door slammed. “That’s mine!” a girlish yell exclaimed angrily. The ladies were home. “Reya, give that back to your sister, she found it,” Raylene admonished. Remy, our three year old, slid open the back screen door and ran out with a purple plastic egg in her outstretched hand. “Daddy lookit I found.” “Leftover from the egg hunt this morning?” She nodded vigorously. “See, it had dis.” It was a small plastic dinosaur. “Very nice.” “I haffa wash my hands now.” She ran off and was replaced by her older sister, who seemed upset. “Let your sister have her toy. She’s little and it means a lot to her,” I said. “It’s not that,” Reya replied, before disappearing back inside. Raylene appeared last. She lifted the champagne bottle and swished it. “Empty, huh? I thought we finished it at breakfast.” “Nope. It was flat, but why not?” I smiled at her as she leaned against the patio cover post. “You look good in yellow.” “Oh this?” Raylene plucked at her dress with two fingers. “It matches my hair,” she said with an affected coquettishness before flipping her locks with one hand. She knew what she was doing. Despite her moments of self-doubt, my wife knew she was hot. I got up and put my arm around her. “You know what that does to me.” She giggled in response. “What was Reya’s problem? Upset over the toy?” “No, that was just the girls being kids.” She paused and dramatically drew a deep breath. “Some homeless guy came out of the bushes and started yelling. He got pretty aggressive and all the kids got scared, especially Reya.” Reya was old enough to understand that last fall we were in actual danger from the burglars and looters. She never quite bought her mother’s lie of Dad-scaring-off-the-bad-guys-with-his-gun though she hadn’t said as much to her children’s therapist yet. “What?” I squeezed her more tightly. “It’s okay. He never got into the playground or close to the girls and I got them out of there. One of the other moms yelled at him and threatened him with her pepper spray.” “Did you have your gun?” She pushed me away. “Ross, did I have my gun? No, I didn’t because I didn’t expect anything like that to happen in our upper class gated housing development in freakin’ Red Rock City.” Being hours away from the major cities made being homeless here very unattractive, consequently our population of raving derelicts was quite small. “What was I gonna do, shoot him for yelling?” she said defensively. “What if he had a knife? What if he wanted to kidnap a kid?” “But nothing happened.” “That’s not the point.” I opened my mouth to give her The Speech but she put her finger on my lips. “Next time I’ll take my purse, I promise.” “Your purse?” I might be late to joining the concealed carry community but women shouldn’t be carrying guns in their purses. Too easy for the whole thing to be stolen, too hard to retrieve the gun, and the kids could get at it. “Ross, where do I put it in a dress?” She struck a pose again, probably to distract me from the barrage of questions I had and a potential unnecessary lecture. Her attempts at using feminine charm failed to deter my interrogation. Some crusty homeless dude, who according to one of the other moms lived in the adjoining brushy gully (aka “the green spot”), was wandering around the community center parking lot yelling and talking to himself. When he started off towards the playground cussing out his invisible enemies, some Karen began to bitch him out, which was entirely appropriate. Yet because Fruit Loops was firing on faulty cylinders he decided that Karen must be his enemy too and got louder while throwing karate poses. The guy cleared off far enough that it was safe for everyone to get in their cars. Nevertheless, little kids don’t like being yelled at by an adult male who hadn’t bathed since the Superbowl and was accusing them of being demons in skin suits. “So she called the cops, right?” I asked. “That’s what she said,” Raylene replied, annoyed I was still asking questions. I got up out of my chair. “I’m going over there to talk to them.” “Don’t do anything stupid,” she cautioned. “I just want to have a chat with the officers, that’s all.” Actually, I wanted to go over there, find the crazy fucker, hit him with my car, then bash his teeth in with a tire iron. Blood spattered in my mind’s eye. No, that would be, as the courts like to call it, malice aforethought. If I came upon the guy, I could just stop and have a few words with him. Ask him politely to leave the kids alone and go away, never to return. Should he get aggressive and put his hands on me, which he would according to the way I was phrasing my words in my head, I’d pull out my pistol and shoot him. Nah, bad idea. You’ve killed three people already. The detectives might think it was more than a coincidence. This wasn’t the first time something like this had happened. A few weeks ago, officers were called because a homeless man, possibly the same one, was walking in circles on the tennis courts yelling at someone who wasn’t there. Nothing happened—the local rumor mill would have blown up if the cops had so much as cuffed him up—but a few kids from the after school program the HOA put on were scared by it. Come to think of it, the condoms found in the play structure probably weren’t from some randy teens. The burglary of the (empty) snack bar was probably a bum too. The infestation had finally arrived here. When our marriage was brand new and we were dumb enough to live in my condo in River City (back before we moved across the river to the island), the national homeless crisis had already begun. We found needles in the city park that we took baby Reya too; sorta like finding rat turds in the pantry. Raylene didn’t particularly enjoy wondering if the raving derelicts on the jogging path were arguing with their hallucinations or about to turn their wrath on her. Back then, she didn’t carry a gun. Three minutes later I was over at the park and saw no sign of anyone. The only motion was the pastel balloons bobbing on their strings tied to the fence and some crepe paper from the morning’s festivities blowing in the wind. The douchebag scared off the kids who were having fun on a freakin’ holiday. I did a loop down to the gatehouse and didn’t see any cops, but to be fair they could have responded to the reporting party’s house. Damn it. I felt betrayed. We felt safe here. It seems the decadence of the 21st century was at our doorstep again. Our new place was a comfortable house in the center of the development, in the middle of the block, with no “littoral” space like a drainage ditch or walking path behind it. Unlike our last house in West River City, this one did not back up to a golf course. The whole development was built on a bluff that sat undeveloped since the area was founded. Until the housing boom started the only thing the owner used the rocky, grassy land for was grazing sheep. The sale of our old house on the island was surprisingly easy and we didn’t take a bath on the price either. The buyer was a middle-aged couple with kids who endured the hellish few weeks across the river and wanted out of the city. To them and to us, “getting out of the city” were different things. Having a bridge and a hundred yards of water between them and River City was enough. For Raylene and me, it meant a house in a gated community in an exurb in the high desert two hours away. While our new neighborhood wasn’t impregnable, it certainly was formidable. Cliffs and hillsides ringed the perimeter so anyone trying to make unauthorized access would need to negotiate a barbed wire fence before climbing the rocky slopes. A few gullies intruded into this natural palisade but these were so choked with thick, thorny brush only determined attackers would use them. Easy enough to surveille those. There was one major point of concern, a small but broad canyon that formed the drainage for the bluff. The community’s clubhouse, swimming pool, and tennis courts sat next to it. The little bit of greenery there made the area feel more remote and natural than it was, which led to the one house for sale overlooking it selling for a premium price. The green spot’s runoff connected with a creek at the bottom and the undeveloped area around it formed part of the city’s park and greenbelt system. Anyone taking the walking/biking trail along the creek could duck through the fence into the gully. Use trails cut through the brush where teenagers and the homeless over the years penetrated it. Do teens still sneak off to hide in the bushes so they can drink without getting caught? I wondered. Both Raylene and I had been teens in the late ‘90s and both of us knew all the hiding places our peers used for getting “faded” or for awkward, sticky juvenile trysts. What the hell were bums doing in there? Getting high, I bet. For a homeless camp, it was a rather remote place. Usually they’re closer to running water, stores, and services. The nearest shopping center was at least two miles’ walk from here. They’re using the clubhouse, I realized. The bathrooms were unlocked and camera coverage of the pool area was minimal. One of them might even have a sillcock key for the hose bibs. Police interference would be minimal if they kept a low profile. The area was inaccessible by road except through the complex. Our development served on one side as a buffer for them and the vegetated area of the creek-side preserve below as another. It was too far for curious kids to hike to from the nearby housing tracts, even though there was a bridge across to the multiuse trail. The junkies could sneak away from better policed camps and do their drugs here without intervention. I stared at that bit of green. It was no longer a preserved bit of the natural, desert environment that survived the onslaught of the unrestrained housing booms of the past two decades. Today the canyon was nothing but a gash right through to the heart of our rocky bastion. Who knows what the tangle of scrubby brush held in that two acre triangle? Chill out. I realized I was staring at the gully the way a terrified little kid assumed a closet held monsters. Easter Fifteen minutes after I left on my patrol, I was back at home. I forced myself to relax. No real harm had been done, the guy left or the cops ran him off, and if I got in serious trouble at least two ex-soldiers, one of whom was a credentialed federal agent, could be here in ten minutes armed to the teeth. Still, Red Rock was supposed to be the city where we could get away from all the failings of western civilization as embodied by the modern American city, or “blue hive” as they called it here. I cracked a beer—because why not?—and went in to the living room, plopping down next to Raylene on the couch. Some Technicolor musical was playing on the TV. “What are you watching?” “Easter Parade. Judy Garland and Fred Astaire.” “Ugh, I hate campy musicals. So sappy.” “Hey, I like this. It reminds me of my grandma. She used to watch this every Easter.” Raylene’s grandmother raised her after her parents split when her dad walked out. He had been schizo like the junkie too. Her grandma died not long after she flew to California for college. Yeah, I just took a big, fat dump on one of my wife’s fondest memories. I’m a jerk like that sometimes. “Sorry.” I kissed her on the cheek. She kissed me back. “Where are the girls?” “Napping.” “Napping?” “They were on the tail end of a major sugar high. It was inevitable. It’s why they were so crabby, apart from meeting the real life Oscar the Grouch.” “Oscar lives in a trash can, not a tent in the bushes.” She ignored me. “Why did you let them have so much candy? “Oh please, if it was solely up to you they’d barely finish their Easter candy in time for Halloween.” One piece of candy a day was no way for a child to live. She clucked her tongue in protest. “I’m not a monster, besides, you let Remy eat an entire package of Peeps right before church. I was so embarrassed.” We had to leave church early because after running around during worship, Remy threw a tantrum and started that screaming-crying thing three year olds do right before communion. It was kinda embarrassing but we were far from the only family with kids hopped up on sugar. “What time do we eat?” “Grant said to be there by three.” Easter was late this year and consequently it would be a warm one. The mercury was set to push over 80° so my brother decided to throw a barbecue. “Heather cooks better than I do,” Raylene said of my sister-in-law. “That’s not true. You both cook very well. It’s just that you both excel at different things.” Raylene tended to use more vegetables in her dishes whereas Heather considered cheese to be its own food group. “And Sadie bakes better than I do.” “If Sadie isn’t careful, all those cakes and cookies are gonna go straight to her ass.” Raylene busted up laughing at that one. My wife was a petite thing and the fattest she ever got was when she had babies inside her. This woman could hoover up everything in sight and not gain a pound. “Yeah, but no one is ever ‘Wow Raylene, this is the best garlic parmesan zucchini I’ve ever had.’ All the roasted, sweetened carrot medallions might get eaten but they all praise Heather’s diabetes casserole.” She changed the tone of her voice to imitate a conversation between two women. “‘So Raylene, what are you bringing?’ Honey butter carrots, grilled asparagus, bacon sautéed Brussel sprouts, and a Caesar salad.” Her voice dropped an octave below normal. “Vegetable side dishes, everyone’s favorite,” she said, slightly discouraged. “Just make sure everyone sees you eat a lot of meat so they don’t think you’ve gone vegan,” I said. “Oh, real reassuring Ross, thank you.” “Do I detect a note of sarcasm?” What was I supposed to do, validate her insecurities? “If sarcasm was oil you just discovered Saudi Arabia,” she replied. I leaned over and kissed her. How could you not love a woman with a wit like that? Despite Raylene’s fondness for organic foods and serving us vegetables instead of grain-based carbohydrates, she wasn’t a vegetarian. This chick loved meat and I’m not talking in the bedroom. If steak and bourbon was on the table, it wasn’t at my place setting. I loved these little particulars about her from her penchant for USDA prime beef, good booze, and old films. Sitting and watching a sentimental movie with her was like being shown into a secret place. Eventually, Judy Garland and Fred Astaire strolled down Fifth Avenue in their Easter bonnets and it was time to go. Raylene woke the girls. They were both groggy, but more tired than ornery and compliantly climbed into their car seats. In the kitchen, Raylene thrust a foil-covered baking tray towards me. “Here, take the hot cross buns.” “Should I have a towel or oven mitts or something?” “They’re cool.” “Then how are they hot cross buns?” “I’ll pop them in Heather’s oven before dessert and then pipe the cream cheese frosting on before serving.” My brother and his wife lived a few minutes across town. The “for sale” sign that had been on the front lawn was gone now that the house was in escrow. After most of a decade, they’d be moving on. Ethan was taking a Department of Defense contractor job out at the arsenal a ways from the city and moving into the adjoining small town. Following the riots that engulfed Red Rock City last fall, I was surprised that anyone would want to buy a house in a place that went through a literal communist revolution (well, a failed one), but the market forces that brought a buyer to our house downstate brought buyers up here. I mean we moved here, didn’t we? By the time we parked our girls were fully awake and cheerfully ran into the house to see what treats awaited them. “Do you like my dress, Aunt Heather?” Reya said, spinning in a circle. Remy attempted to imitate the spin but bumped into the china hutch. “Your dresses are lovely, my dears. Why don’t you and your sister go watch TV with your cousin Ella?” “Okay!” I left the women to it and went outside where Grant was at the grill. “Hot dogs; isn’t that more of a Memorial Day kinda thing?” I cracked open a beer. “It’s a barbecue. Do you really think the girls are going to get excited over smoked ham and brisket?” I shrugged. “Dunno. I’m excited.” He started chuckling. “Only adults would go ‘Oh boy, smoked meats!’” We both laughed. I told him about what happened to Raylene and the girls at the park. As the story went on, he grimaced and gritted his teeth in vicarious anger. “Did you break his teeth in?” he asked when I finished. “I went looking for him, but no dice.” “What are you gonna do about it?” His question was not exploratory. He did not want to know what my feelings or inclinations were. Grant was asking what my plan was. “Haven’t decided yet. I need to talk to your other two guests first.” “Good idea.” Those other two guests, Ethan and Sadie, were the last to the party. Ethan was a federal agent with some obscure agency and Sadie was a cop for the city police department. As a student resource officer, she seemed hardly older than the high school students she dealt with but was a decade older than the seniors. Both Sadie and Raylene were athletic and attractive. Sadie was curvy and muscular, “stacked” as the kids these days would say, while Raylene was slim and had a runner’s physique. I wondered which one would be faster on her feet. Probably a bad idea to race wives, I thought. “Ethan burned himself,” Saide announced loudly from the kitchen. “Do you have any ice?” she asked Heather. “Dumbass,” Grant said without looking up from the grill. I stepped away and filled up a plate with hors d’oeuvres. I mean not the kind that you get at a fancy catered dinner or five-star restaurant, but standard American middle-class fare. Deviled eggs, chips and dip, veggies and ranch, cream cheese pinwheels, and the like. Yeah, I’m built like Homer Simpson and probably should just be eating raw carrot and celery sticks, but you know what, it’s a holiday and my wife likes stocky guys for some reason. “Glad to see you like those, Ross,” a voice said behind me. I turned. “Huh,” I mumbled to Sadie with a mouthful of her deviled egg. I held up one finger while I finished chewing and swallowing. “Good eggs. Very tangy.” “The secret is lots of dill and relish.” “Nice touch. Where’s Ethan?” “Thanks. He’s icing his arm. I told him to wrap a towel around the Spinach dip but no, he had to manhandle it and got burned. Serves him right.” “No way a man is going to make two trips if he can help it.” She thought that was funny. “Say, can I ask you a legal question?” “No segue, clever.” She was used to people coming up to her in public and asking questions at inopportune times like having just taken a bite of a sandwich, so why not me? “What’s up? Want a carry permit for your flamethrower?” Light up looters just once with a modified weed torch and a 20lb propane canister and you become the butt of jokes. When it went down, my shotgun was in evidence and my pistol upstairs with Raylene. In probably the most inopportune week of my life, I had no long arm to defend myself with and all the gun stores were either sold out or closed on account of a combination disaster and mass rioting. So with a little creativity in the garage, and some teenager on YouTube as my tutor (seriously), I turned myself into a dragon. That thing was seriously sketchy. An ex-Army friend-of-a-friend suggested his solution, an electric pressure washer filled with diesel, but at the time electricity and diesel was in short supply. Had I owned a damn rifle then, I’d never would have had to resort to MacGyvering my self-defense. “So what can be done about the homeless people living in the bushes near our neighborhood?” I asked. “Practically speaking nothing. We don’t have enough cops to shake the bushes and scare them out.” In the aftermath of the riots last fall, Red Rock PD suffered catastrophic retention losses and could barely respond to normal calls for service. A public service task force was so 2019. “Legally speaking, depending on the area, trespassing. Anytime you contact the homeless you’ve got a pretty good chance of coming across one who’s on probation, has a warrant, or has drugs on them. Those incidental violations aren’t bad. Pop ‘em for possession of a controlled substance. Maybe a camping violation.” “So what, I call and you guys come and write them a citation?” “If you’re lucky. To be honest with you Ross the dispatcher might just reject the call if they aren’t causing some sort of imminent danger.” “What about yelling at the kids?” I told her about the scumbag yelling at Reya. “Did he make actionable statements of imminent harm?” “I see your point.” “Look, if one of them gets pissy with you or the kids, give me a call. If I’m free I’ll swing by and do whatever I can, but we simply don’t have the manpower or the will anymore to comb the bushes and clean them out.” “Thanks.” I sank desultorily into the lounge chair and watched my brother poke at the meat on the grill. Gee, Ross, we’d love to help you, but the police department is so dysfunctional you’re lucky that 9-1-1 gets answered. I couldn’t be bitter at Sadie. We all knew her mind on the topic and she wasn’t a member of the fake-it-‘til-you-get-your-pension squad. A few minutes later Ethan emerged with a Ziploc bag full of ice cubes pressed to his forearm. He and my brother had served in the Army together and was in fact family at this point. “Afternoon, gents,” Ethan said, grabbing a beer with his free hand and taking a seat at the patio table. “So, find a house yet?” Grant looked up from the meat he was putting on a platter. “Sorta. Bought five acres that back up right to Army property so nothing is ever getting built behind us. There’s no house on it, but we found a real nice place to rent in town for a few months until we can move in.” Now that the meat was done, the women began to bring out the side dishes for the meal. The entree was smoked ham, brisket, and hot dogs for the kids. The sides were potatoes au gratin, macaroni and cheese, Raylene's bacon sautéed miso Brussels sprouts, honey butter carrots, and grilled asparagus. Caesar salad too. For dessert Sadie's carrot cake and Raylene's hot cross buns with raisins and cream cheese frosting were waiting. After the blessing, Ethan asked “Hey, anyone else find it strange that ham is like an Easter staple? I mean Jesus was Jewish.” Grant forked himself over a slice of ham. “Dude, it’s not like we’re eating lamb.” “I don’t like lamb,” Sadie said. “Too gamey.” “That’s because it’s mostly Australian or New Zealand sourced meat,” Heather explained. “There they feed the animals grass, which gives it that flavor. American lamb is fed on grain so it tastes more like beef. You know, sweeter.” “Well, lamb is pretty popular in the Middle East,” Raylene said. “So is goat but they aren’t eating the goats they’re—” Ethan was cut off by the audible sound of Sadie slapping her new husband. “There’s children around,” she admonished. Ethan looked guilty for a second and began eating. “Custom house, huh?” Sadie asked, picking up the earlier conversation, eager to hear the details about the other Porters’ new home. “It’s a modular home,” Heather said. “A real nice one. 2,500 square feet. Four beds, three and a half baths.” “You’d never know from the pictures that they truck it in,” Grant said. “Don’t say it, don’t say it,” Heather said to him while doing that thing where women didn’t make eye contact. “It’s a triple wide,” Grant said with a grin. “I told you not to say it.” “It was the cheapest and fastest option to get a house. The design we picked has pretty much everything we want and we’re having a large garage/shop built next to it. We’ll end up having more room than we’ll possibly need.” He turned around and continued taking the meat from the smoker. “Ross, I told you, rather than spend hundreds of thousands moving into another city, you shoulda built a compound with us.” “I need reliable ultra-high speed Internet to do my job,” I said defensively. I am a senior executive for a very high grossing IT company and work remotely. DSL or Starlink in the sticks wouldn’t cut it. “Tell you what, we’ll build a little cabin in the back next to Ethan’s shack.” “It’s not a shack, it’s a tiny home,” Ethan said. He was still a little self-conscious that I made at least triple what he did. His savings had gone into paying off Sadie’s mortgage in exchange for getting his name added to the deed and her changing her last name. Rural properties were selling like crazy in Fremont. After the floods and riots of last year, plus the fact we were in the early stages of a real civil war, no one wanted to be in the cities. Those in the metros, like Raylene and me, were moving to the exurbs, and those in exurban cities were moving to the sticks. The further from desperate people, the better. Desperate people like the crazy homeless guy. My wife told the story to the whole table. Ethan and Heather hadn’t heard it yet. Raylene added in new details she hadn’t told me, like how the douchebag was cussing so the kids could hear it and even making grabbing motions, though it was on the other side of the fence. I took my building rage out on my meat, which I cut into unsatisfyingly small portions. Finally, I couldn’t handle it anymore. “You know what? Screw these people. They make a choice not to take their meds, then they act like animals, and them I’m expected to show sympathy for them? No. These same moms that are up in arms about this guy are probably the same ones that got mad when the camp under the Interstate got cleared out a few weeks ago and the state threw away all their stuff in dumpsters. If this was a feral pitbull that bit some kid, they’d want the dog destroyed. Okay? We don’t treat stray animals like this.” I was primed to say more, but my wife grabbed my arm and shot me a look that could freeze water in the Sahara. “Isn’t there a shelter they can go to?” Raylene asked. She was our California-educated crunchy granola hippie family member after all. Sadie answered. “Yes, but it’s small and can only handle a large influx in winter or summer when it’s triple digits. That’s when they open the overflow hall, but honestly, few of them want to go there. Shelters have rules, like ‘Sir, please don’t shoot up Fentanyl on your cot.’ Or some don’t like that they can’t drink malt liquor in there. They’d prefer to camp out where they can do whatever they want, even if they go hungry.” “Really?” Raylene asked. “Yeah, really,” Sadie said, aggressively stabbing at her salad. “I know everybody thinks that homeless people are just down on their luck and need a helping hand, but that’s crap. Those kind live in their cars and the only time we have trouble with them is a parking complaint. Then they apologize to the traffic cadets and move somewhere else. Our last survey showed about a hundred regular homeless people here and most of them are mentally ill drug addicts.” “Both?” Heather asked in surprise. “Yep. Some of the strong psych meds can have really nasty side effects so they prefer to just get high or stay drunk to deal with the voices or whatever. Being strung out is better than feeling like a zombie or whatever on what the docs give them.” “Can’t they be forced into therapy or a hospital or something?” “What hospitals? They closed most of those in the ‘80s. You gotta be really sick to get institutionalized for good now. For addiction? Forget it. The laws are getting slightly better, but there simply is no infrastructure in this country to house the mentally ill or drug addicts. The best we can do is take a problem character off the street for a few hours or days until he calms down.” I mumbled something about liberals and do-gooders and forked some food in my mouth. Ideas were brewing in my head and it would be best to let the topic drop. Deliberation On Easter Monday I did a little reconnaissance. Fences could be climbed and cut and ours were. The perimeter chain link fence had a human-sized hole in it and the bottom strand of the city’s barbed wire had been snipped. I already saw a work order created for it on the HOA maintenance webpage so we were good in the short term. Still, that was no guarantee the fence would stay uncut. Grant’s voice echoed in my head: “An obstacle not enforced by fire is not an obstacle.” All it would take was a junkie who wanted to use the park toilets or break into cars and the perimeter would be breached again. Something more drastic was needed; something that would also send a message. I thought about electrifying the fence where they were making entry. There was always the legitimate option of talking to the HOA to see if they would do it. Given the panic over the riots last year, I’m sure some outraged mom would be bloodthirsty enough to second the motion. Scare yuppies badly enough and they’ll flip all the way to “Get off my lawn” in no time flat. One of the bleeding hearts who couldn’t handle the change in attitude around here actually sold us our house, but I digress. Challenges involved cost, signage, maintenance, and the inevitable question of “Who’s gonna pay for that?” And although the tolerance towards anti-social behavior in Red Rock was extremely low, there would be at least one lawyer that would nix the idea. Were electric fences even legal in this state? I had no clue. Now I could do it myself on the sly. The DIY solution of jumper cables and a car battery seemed like a great way to electrocute myself. For a couple hundred bucks more at Tractor Supply Co. and I’d be in business with less of widowing my wife. Either way, it wouldn’t be a long-lasting solution once the bums obtained some insulated wire cutters or found and destroyed the charger. So without bug-zapping our unwanted guests, I needed another solution. Whatever it was, it had to be deniable if it carried even the slightest hint of criminal or civil liability. No sense getting sued by an ambulance chaser because the mountain lion I released ate a homeless guy’s leg. My criteria was: