|

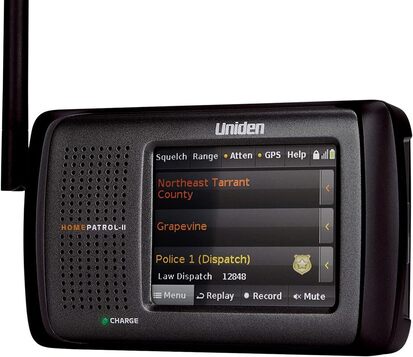

In the world of radio enthusiasts and scanner aficionados, the Uniden Home Patrol 2 stands out as offering unmatched convenience and functionality. With its user-friendly design and powerful trunking capabilities, this scanner is a game-changer for those who want to dive into the world of scanning without the need for a master's degree in radio programming. In this blog post, we'll explore why the Uniden Home Patrol 2 is the ultimate choice for anyone seeking effortless trunking capabilities.

Trunking Demystified Before delving into the features of the Home Patrol 2, let's briefly understand what trunking actually is. Trunking is a method used by various radio communication systems to optimize frequency utilization. Traditional scanners can struggle to follow these complex systems, often requiring intricate programming knowledge. This is where the Home Patrol 2 steps in, eliminating the need for in-depth technical expertise. Note that your $70 Radio Shack analog scanner CANNOT receive trunked radio systems. User-Friendly Interface The Uniden Home Patrol 2 prides itself on its intuitive user interface. It's designed with the average person in mind, making it easy for beginners to get started without feeling overwhelmed. The touch screen display guides users through the setup process and scanning options, ensuring a smooth experience even for those with limited technical know-how. Simple Set-Up Gone are the days of spending hours deciphering manuals and trying to configure intricate scanner settings. The Home Patrol 2 boasts a hassle-free setup process. Users can simply enter their location and let the scanner do the rest. The device automatically identifies and loads the frequencies for nearby agencies, making the entire process a breeze. Database Integration One of the standout features of the Home Patrol 2 is its extensive database integration. Regular updates ensure that the scanner has the most up-to-date frequency information for various agencies, including police, fire, EMS, and more. This means you'll always be in the know about what's happening in your area. Dynamic Memory Allocation The scanner's dynamic memory allocation is another factor that sets it apart. It automatically allocates memory to active channels, optimizing your scanner's performance and ensuring you never miss a crucial communication. GPS Support With built-in GPS support, the Home Patrol 2 takes convenience to another level. As you move around, the scanner automatically adjusts its settings to provide you with relevant local channels. This is particularly beneficial for road trips and travel, as you'll always have access to the most pertinent information. Trunking Made Easy As our tagline suggests, the Home Patrol 2 is the perfect choice for individuals who want trunking capabilities without the complexities of radio programming. It handles trunking systems seamlessly, allowing you to monitor conversations across different frequencies and agencies without the need for manual intervention. The Uniden Home Patrol 2 is a game-changer in the world of scanners, especially for those who crave the convenience of trunking capabilities without the steep learning curve. Its user-friendly interface, simple setup, extensive database integration, dynamic memory allocation, GPS support, and effortless trunking handling make it the best scanner for both beginners and experienced users. If you want a scanner without the need for a master's in radio programming, the Uniden Home Patrol 2 is your best option. Author’s note: the accounts mentioned in this article are taken from Falkland Islanders at War by Graham Bound (2006), published by Pen & Sword Military.

Imagine you live in a remote, small community that is invaded one day by a vastly superior military power to the local token military/militia forces. How would you communicate with your neighbors or your own military? How would you gather and send intelligence? What tricks could you play with ham radio? In 1982, for the residents of a remote British colony, this was no thought exercise. Far south in the Atlantic, off the eastern tip of South America, sits the rocky, windswept Falkland Islands. Half the world away from Great Britain, this little outpost of Albion was the subject of a brief, nasty war in 1982 when Argentina invaded what they call (and claim) “Islas Malvinas.” Make no mistake; as trivial was this footnote in history may have seemed on the news, it was a real war with ferocious fighting, heroism, and daring risks taken by the islanders. The Falklands had been little more than an outpost for the wool trade and a stopover for ships since Britan colonized the islands in the 1830s, following a brief attempt at settlement from Argentina that was abandoned. Despite the islands having little to no strategic value, these treeless islands that resembled Scotland were in a natural position for neighboring Argentina to claim them. In the decades leading up to the war, the UK and Argentina had tried various means of rapprochement over the islands. In an era of decolonization it really did seem like Whitehall wanted to give the territory over to Argentina. One could almost call the islands neglected by their motherland where, at the time, the almost entirely British-heritage population was denied full British citizenship. Despite all this, the islanders felt themselves to be British, even those whose families left the UK generations ago. No islander wanted to be handed over to Argentina like a dirty memory of the colonial past only to be under the heel of a military dictatorship. The green-eyed suitor was decidedly a worse choice than the inattentive UK. Argentina was currently governed by a military coup known as the Junta in the years following its Dirty War against what we would call progressivism. It is argued with much merit that the war was launched as a distraction against public dissatisfaction with the Junta’s repression and economic policies. While readers may sympathize with the Junta’s heavy hand against socialist forces at home (throwing communists out of helicopters), the totalitarian tactics bled into the occupation force’s behavior towards the civilians islanders. Thankfully, aside from some selected abuses, the invaders remained fairly well restrained towards the “kelpers” who endured the two-and-half month war. However, the suspicion, and treatment, of civilians was harsh but thankfully not deadly. Death for the islanders who resisted would have been an easy stretch for Argentina. However, reprisals of this type were nil. Knowing that the small detachment of Royal Marines, about 40 (as a troop exchange was happening at that time), and small Defense Force would be overwhelmingly outnumbered, Governor Rex Hunt ordered that there be no guerilla warfare. The help the islanders did provide through intelligence gathering, minor sabotage, and scouting was invaluable to the British task force. This article looks at the use of radios by civilians. The accounts highlight the risk of radio operation in a non-permissive environment. There were many intrepid islanders who, at great risk to themselves, passed intelligence back to Britain and even interfered with Argentine communications. Radio is a powerful tool of resistance and some plucky kelpers used it to good effect. Radio communication was, and still is, a way of life in the Falklands. The islands consist of one major settlement (Stanley), numerous hamlets, and isolated sheep farms across approximately 4,000 square miles of the two main land masses. Especially in the 1980s, communication was largely by radio as the telephone exchange only worked in the city. 2-meter radio formed the backbone of the “bush telegraph” communication system as their form of citizen’s band radio. Many islanders also had high-frequency (HF) radio sets to communicate over longer distances, with ships, and to the outside world. Families owned multiple VHF radios. Sets were in every vehicle. Longer-ranged sets provided communication across the craggy islands and even across the world. Total confiscation, even with registration, would never be possible due to their prevalence, proliferation, necessity, and the huge distance required to reach remote settlements. The Argentine occupation government realized this and allowed rural radios mainly for the purpose of radio consultation with doctors during their regular “radio surgery.” The islands’ radio operators were apparently all licensed. In such a small place, although enforcement probably was not much of a concern, unlicensed transmission would be obvious among such a tiny population. Records of operators’ licenses were kept at the Post Office which meant that once the islands fell to the Argentines, intelligence officers seized these records. Immediately the security officials knew not only who was licensed but the particulars of their equipment. At once, we see the problem of government registration and licensing; it is a roadmap for confiscation and harassment. Americans tend to think in terms of firearms but the same problems we fear over guns the islanders faced with radios. Sad Hams delight in government approval and tracking, but its easy to see how gatekeeping can be a liability during exigencies. Once the order to turn in radio sets was broadcast via the local commercial radio station, it would be easy for military police to raid the homes of those who failed to comply with the order. House-to-house searches to check compliance and even searches for clandestine transmitters was commonplace throughout the war. The level of fear of illicit transmissions the Argentines had belied the actual level of spying that went on, at least up until the final counter-assault. While Sad Hams are proud that they are registered with the government, such behavior can be a double-edged sword. Americans may not face the same prospects of invasion as the islanders did, but one can imagine how a registry could be used inappropriately. One benefit to the American scheme in combination with the advance of modern technology is that individual equipment is not registered and it is quite affordable to have separate radio sets, particular dual-band VHF/UHF sets like the Baofeng. Unaccounted for sets are a buffer against confiscation, which one fortunate islander used to his advantage. Lighthouse keeper Reginald Silvey, shortly after the invasion began, made a contact on the 15m band and passed a simple message to his relatives through an English ham 7,800 miles away. What began as a desperate dispatch to family, turned into the passing of actual intelligence to British defense authorities, requiring a cat-and-mouse game to outfox the Argentinian communications specialists. Ostensibly, Silvey complied with the military orders and surrendered his transceiver. Silvey turned in his registered radio and made “a fuss” when handing it in. He intended to make it memorable so to remove any suspicion that he had a transceiver. Additionally, he tore down his large antenna. During the dismantling process, a helicopter flew by and he and his friend were sure to wave to make sure the work was noticed. To get around the problem of radio confiscation, he turned to his friend George. George captained a small ship and his HF radio had not been taken out of his ship. He retrieved it in secret, using a subterfuge to access the restricted waterfront, and smuggled it into a hiding place for Silvey to receive. Should the Argentinians notice the radio was missing from its place on the ship’s bridge, George would claim that while the ship was unattended, soldiers stole it—an entirely plausible answer. Two problems now confronted Silvey; a power supply and an antenna. For the former, he turned other friends who drove hospital Land Rovers. A 12-volt battery was delivered that would provide power for the rest of the war. For an antenna, the steel clothesline made do, although it was not ideally matched to the frequency. Argentine troops still raided homes on a daily basis which meant Silvey was at risk. A pass issued by the commanding general, Mendez, served to notify troops that the house had been cleared and that they should not enter, although this was not an ironclad guarantee. Silvey, now back on the air, made contact with a Briton who passed intelligence on to the Ministry of Defense. From his window, the lighthouse keeper could see the airport and wanted the authorities to know that the area, packed with troops and supplies, could be attacked without harming civilians. Following messages contained counts of weapon emplacements and their locations. One important bit of info passed on was the presence of a surface-to-air missile (SAM) launcher near the airport. The authoritarian military occupation forces were quite serious about stopping illicit radio transmissions although their reach exceeded their grasp. Direction-finding vans combed the only city and capitol of Stanley as well as the rural portions of the island, known as the “camp.” Aiding his evasion of the foxhunters, Silvey used terrain against the Argentinians. Despite some islanders who were very remote from the bulk of the troops in town, Silvey sat on Cape Pembroke only five miles away. However, terrain, propagation physics, and human nature were somewhat in his favor. First of all, the Argentinians were focused mainly on short-range VHF (2m) transmissions as this was the most common form of radio used in the islands. A major concern was local communicating with missing Royal Marines or SAS/SBS commandoes landed on the island to conduct reconnaissance. Hence the focus was less on high-frequency (HF) radio. Direction finding (triangulation) of radio signals is affected by terrain, which can block both the propagation of transmitted signals and inhibit reception. Stanley is sited on the slope of a hill above a bay, which would place it below Silvey’s radio horizon (and that of much of the island). Putting terrain features between the transmitter and an interceptor can be an effective tactic, depending on the antenna, the band’s propagation characteristics, and other factors. HF signals, being subject to ionospheric variations and skywave propagation, may exhibit non-linear paths and inconsistent signal strengths over different paths. This can introduce errors and uncertainties in triangulation calculations, making it more challenging to precisely determine the source location. On the other hand, VHF signals' line-of-sight propagation provides more predictable and direct paths, allowing for more accurate signal source triangulation. Signal source triangulation requires the use of multiple receivers to measure the signal arrival times and calculate the intersection point of the signal paths. While the propagation characteristics play a significant role, other factors like receiver accuracy, timing synchronization, and environmental conditions also influence the overall accuracy of the triangulation process. Hence at least two mobile vans would be required to narrow down the suspected transmission location for house-to-house searches. Silvey transmitted using a mixture of voice and morse code. His signals were often sent “in the blind”, that is transmitting without first establishing that someone is actually receiving. GCHQ, the UK’s version of the NSA, with their incredible global radio signal detection capabilities, likely detected these signals once they were aware Silvey was passing transmissions. He also kept his transmissions short (around 15 seconds), which aided being able to evade detection. Longer transmissions give the direction-finders more time to detect and triangulate the signal (lowering the signal strength and using directional antennas, in line-of-sight bands, also decrease the probability of interception). Other islanders reported good results by decreasing their transmitting power to limit the propagation of their signals, thus preventing the distant interception sites/vans from receiving them. Understandably, the Argentines were paranoid about British commandoes spying. Signals were detected, or believed to have been detected, in town by the Argentine foxhunters. However, no actual source was ever found. The area of interest for the electronics crew was some distance from where Silvey was transmitting from. While it is possible that others were transmitting, this information has not been revealed. Several islanders did mention mysterious British men who seemed out of place moving about the town in the later phases of the occupation. As the Paras and the Royal Marines advanced, these mysterious men even made contact with particular islanders apparently making sure that they had not been arrested or killed. Many are certain these were British intelligence officers or commandoes. If MI6 or the armed forces infiltrated spies into Stanley prior to the British counter-invasion, it is still classified. Another tactic Silvey employed was the use of another islander’s call sign, that of Bob McLeod, who lived across East Falkland in the small community of Goose Green. Silvey would drop Bob’s name, well known among hams who sought to make contact with the coveted, remote VP8 callsign. This bit of deliberate misinformation would lead any potential interceptors to assume McLeod was transmitting, which would be impossible since his radio had already been confiscated and himself interned. To this day, this “disinfo” had led people to believe in the legend of “Radio Bob.” In a separate incident, after the residents of Goose Green had been interned, Argentinian troops occupying McLeod’s home came across a photo of him in uniform. McLeod was a member of the Falkland Islands Defense Force, the island militia. Already suspect for being a licensed ham, the occupiers accused him of being a spy. Much pleading had to be done on Bob’s behalf to convince the troops that his radio had already been impounded and he had been confined with everyone else. This the troops should have known, but the Argentinians did not send their best, and many such incidents involving the hair-trigger and largely conscript soldiers occurred. Even if the information provided was not helpful, the continued transmissions forced the Argentines to monitor and hunt civilian radios. This dissipated their efforts which might otherwise have been focused on searching for special forces radioing back to the task force. Even the house-to-house searches that followed ensured that the population remained hostile to the occupiers. A Chilean immigrant, Mario Zuvic, who hated Argentina devised a concealed aerial in a treetop that he and his friends used to listen to Argentinian forward observers on nearby hills. Some of the traffic they intercepted was mundane. Argentinians would be phone patched via radio back to their families. This was the only link, aside from mail, that the mostly conscript army of little more than boys, had with home. Other efforts were considerably more dangerous. Despite all of the interference and the incredible frustration it caused, Mario’s transmitter was never found. In the rolling terrain of the “camp”, it wouldn’t be easy to triangulate the signal. Mario and his friends would send false signals to the occupiers’ radio control center including fake orders to disrupt forward observers. In addition to this, they scanned the airwaves until they detected Argentine radio traffic then jammed the conversation by transmitting at maximum power. After one of the British landing ships was attacked, the following day when it seemed like it would happen again, Mario jammed the frequencies by simply keying the mic. This left the occupiers unable to send messages to their headquarters all day and probably disrupted both attacks on the ships and other combat operations. Not long after an auxiliary airbase was completed at Goose Green, it was attacked by Harriers. Though the anti-air defenses scored one kill, the uneducated troops insisted that there was a spy among the civilians passing radio traffic to the British task force. This resulted in a house-to-house search for the radio that didn’t exist. One little girl even asked her father “Daddy, are we going to be shot?” It is questionable whether or not the Argentines would have executed anyone. Given the lack of physical resistance in the islands and the rather hopeless position the occupying forces were in, it seems unlikely. General Menendez said that anyone caught transmitting intelligence to the British “would have been considered a spy and that that traditional treatment of spies” (being shot) would have been applied. Perhaps if Britain had not moved to recover the islands or if there was an active resistance taking Argentine lives the clandestine radio operators would have been treated more harshly. Even so, Argentinians committed many war crimes, generally conducting or threatening mock executions. One captive civilian in Goose Green tuned a radio to the BBC, but in doing so, came across a conversation between hams. The troops thought that the islanders were somehow communicating with British forces and cocked their weapons threateningly. Eventually the occupation government’s sympathetic civilian administrator intervened and managed to get a senior military officer to parole the men to a hotel. After an incident where an islander attempted to contact the British flotilla, helicopters were loaded with men and radios then flown back to Stanley. At the police station, one man was forced to write a statement and threatened with a knife. Others were taken outside, ordered to dig a trench (presumably) a grave, then forced to kneel in wet grass before soldiers dry-fired pistols in their backs. The brave acts of the islanders during the Falklands War shows that radio is an important tool not only for communication, but for passive resistance. We won’t know for a few more decades what impact the passed intelligence had (until it is declassified) but even if it was redundant, much effort and time was expended by the occupiers trying to counter it. Civilian radios do have a place in creating electronic warfare as long as it is done smartly. And finally, to the consternation of Sad Hams everywhere, registration and licensing leads to confiscation. Always have radios no one knows about hidden away. If this topic intrigued you, also check out NC Scout’s book The Guerrilla's Guide To The Baofeng Radio.

The average person who gets a Baofeng radio will have no idea how to tune in when they turn it on and see an input like 445.000 staring back at them. Pushing the buttons to blindly tune the frequencies up or down doesn’t work like a CB radio, car stereo, or marine radio. You can’t just pick a frequency at random and start using it. First, there will probably be no one to talk to. Second, you could be transmitting on a frequency or in a mode that is prohibited.

My pre-ham radio experience was with VHF law enforcement radios; my agency has 16 channels programmed in on the main ‘A’ bank. For public safety/business use, the FCC assigns frequencies. Not in the ham world. Ham radio does not have defined voice channels like Marine radio, CB, or GMRS/FRS. The concept of saying “Go to channel __” doesn’t exist. What exists on the ham bands are portions of the frequency spectrum that is generally understood to be used for simplex (radio-to-radio) voice communication. Imagine it as a freeway without any marked lanes. To better navigate that lane-less freeway, radio users have decided to separate portions of each band and dedicate them to specific uses. Simplex, or radio-to-radio voice, is just a small part of that. In order for the various uses of the ham bands to all get along, local radio coordinators outline what ranges and frequencies should be used for what. These coordinators are unofficial bodies and the plans aren’t legally mandatory, but they are mostly obeyed to avoid chaos, the same way people obey traffic signals when a cop isn’t around. You can create “lanes” for your own channel plan as long as you play by the rules that everyone else does. This is really no more than agreeing on specific frequencies to use and giving them a name or alpha-numeric designation. Having a channel name or number is for brevity and communication security. “Go to five,” is shorter and more secure than saying “Go to 158.730.” So, within your own group/family, you can know that “VHF channel 1” means 146.415 MHz. Again, this is an in-group thing because there are no public ham channel allocations. How to get startedMy semi-facetious suggestion is become friends with a likeminded, experienced ham and let him provide you with his pre-existing plan. I kid, but there are hams in your community that have already done this and will have saved you a bunch of trouble. Connections can and do pay off. But for the rest of you… Start by finding the basic band plan[1] for the band you plan to use; in our case it will be 70cm or 420-450 MHz UHF. Note that 420-450 MHz is the basic frequency range for that band; it will be divided up into different groups for various uses, such as Morse code (CW), television, etc. Be sure to review the band plan for frequencies that are reserved for specific uses, such as digital packet transmission only, often noted “no voice.” Note the bandwidth spacing for each band. For 70cm, this is 25 kHz while in some parts of California it is 20 kHz. For 2m VHF, this is 15-20 kHz. Think of spacing as a separation lane to keep the radio traffic from bleeding into each other. Too narrow of spacing and the radio signals start interfering with each other. Using the no-lane freeway above, technically speaking is the bandwidth separation. As long as the traffic is within the limits of the range and far enough apart from each other, who talks on what frequency is unregulated. You can simply plug in a frequency in the right range, check that the bandwidth is set properly (the radio should do this automatically), and start talking. Shy of SHTF or an emergency this can be a nuisance. Practically speaking, you need to mind the upper and lower end of the frequencies for both the FCC-defined band and the range for simplex voice. Orderly ham radio depends on everyone coloring (or parking or driving, whatever analogy you prefer) within the lines. One can’t reasonably just start yakking away on any frequency for this reason. This problem with choosing a frequency at random is you may be talking slightly off a locally defined channel and interfering with that traffic. That’s a quick way to make other hams unhappy, sort of like making the other guy pull off a one-way road so you don’t have to get your car’s passenger side all muddy by driving on the shoulder. What needs to be done is see if there are any local channel plans for the band you intend to use. Locate your state or regional band plan. These are gentlemen’s agreements by local ham organizations to allocate the different frequency ranges for various purposes to better regulate and coordinate traffic. Many organizations do not coordinate simplex frequencies. In this case, generic spacing and allocations can be used. You will need to Google “[state or region] ham radio band plan” to find this information. Alternatively, you can ask a local ham club. In the 70cm UHF band, you will want to check your local band plan (down to the county, if there is such an organization) and the repeaters carefully before deciding on using a certain frequency. For example, you may want to start at 445.000 and go up to 446.975 at 25 kHz channel spacing intervals. At each interval you would check that the band plan doesn't reserve the frequency for something like high-speed packet transmission or that it's assigned to a repeater. Note that you don't want to break the pattern of intervals because your signal will bleed over to other frequencies and cause interference with other traffic. That's rude, like parking in two spaces. It's going to make people mad and if you have a problem that comes to the FCC's attention you will be the at-fault party. So once more, random frequency selection is suboptimal. Check your local repeaters to ensure that you are not talking on a repeater input/output frequency. Repeaterbook.com is the most popular resource for repeater information. This becomes more of a concern in 70cm UHF because the simplex (voice) range is shared with repeaters. For instance, in Missouri 445.900–445.975 is shared between simplex and packet traffic; at 25 kHz spacing that leaves four voice UHF channels that can be used. Don’t forget to actually listen to the frequency for a while to determine what kind of traffic is used on it. Finally, remember that the airwaves are all shared and open to the public. There is no privacy or reserving of frequencies. All FCC regulations will apply. Your channels are nothing more than a memory device for certain frequencies and will be specific to your group only. Any outsiders you are communicating with will need to be given the actual frequency to tune to, not your channel number/name.

Repeaters You may want to put repeaters in your channel plan. For instance, my group notes these with an R (Romeo) for repeater, as “31R.” Again, the repeaters are public but saying 31R is easier and more discreet than saying “McClellan Peak UHF” or “W7RHC.” Some notes about programming repeaters in: For repeaters, the input (receiving) frequency is published. This is the frequency that your radio will talk to the repeater on. You will need to program in an offset so the radio knows what frequency to listen for the output signal (that the repeater is re-transmitting the traffic on). Note the offset for your band; this varies. 70cm uses a 5 MHz + or – above or below the repeater input frequency. 2m VHF is 600 kHz or .6 MHz. Most radios will automatically set the offset frequency once you note + or – in the software so you don’t need to manually enter the offset frequency. Most repeaters will use a PL tone to activate the repeater. The offset and PL tone will vary on each repeater. Common simplex voice frequencies 2 Meters (144-148 MHz) 146.400-146.580 simplex 146.520 National simplex calling Frequency 147.420-147.570 simplex 70cm (420-450 MHz) 445.000-447.000 simplex (shared with repeaters and other services) 446.000 National simplex calling Frequency Example 2m simplex channels (SoCal) 144.310-144.375 (15-20 kHz apart) 144.405-144.490 (15-20 kHz apart) 145.510 145.645 145.525 145.660 145.540 146.445 145.555 146.520 (calling freq.) 145.570 146.535 145.585 146.550 145.600 146.580 145.615 146.595 145.630 147.510 https://www.tasma.org/TASMA-2m-Band-Plan.pdf Note that the 70cm UHF equivalent of above is extremely uncommon. Sample band plan This simple band plan is taken from Los Angeles area information. It includes a Channel of the Day (COD) so each group member knows where to go each day to listen and make contact if necessary. While a real plan would have the frequency order switched up, changing the “main” frequency each day will inhibit any easy monitoring by bad guys. Note that the days must rotate because there are not enough frequencies for a 31-day month. Channels of the Day will need to repeat, and more often on bands with lesser available simplex frequencies, especially on UHF. Repeaters that are intended to be used are included as well. This method will work for 2m/1.25m/70cm and GMRS/FRS. A similar plan can be made up for CB with the ordinary channel numbers switched up. The duress channel is an unused frequency that can be switched to if your transmissions are being monitored by bad guys. The code word can be spoke and everyone will know to switch without further prompting. Credit to Andy for coming up with my group’s plan, from which I modeled this example chart (because the public isn’t seeing our actual one). Note: this is an excerpt from my book Basic SHTF Radio: A cop's brief guide for understanding simple solutions for SHTF radio communication, available on Amazon. [1] https://www.arrl.org/band-plan

Don't forget a programming cable.

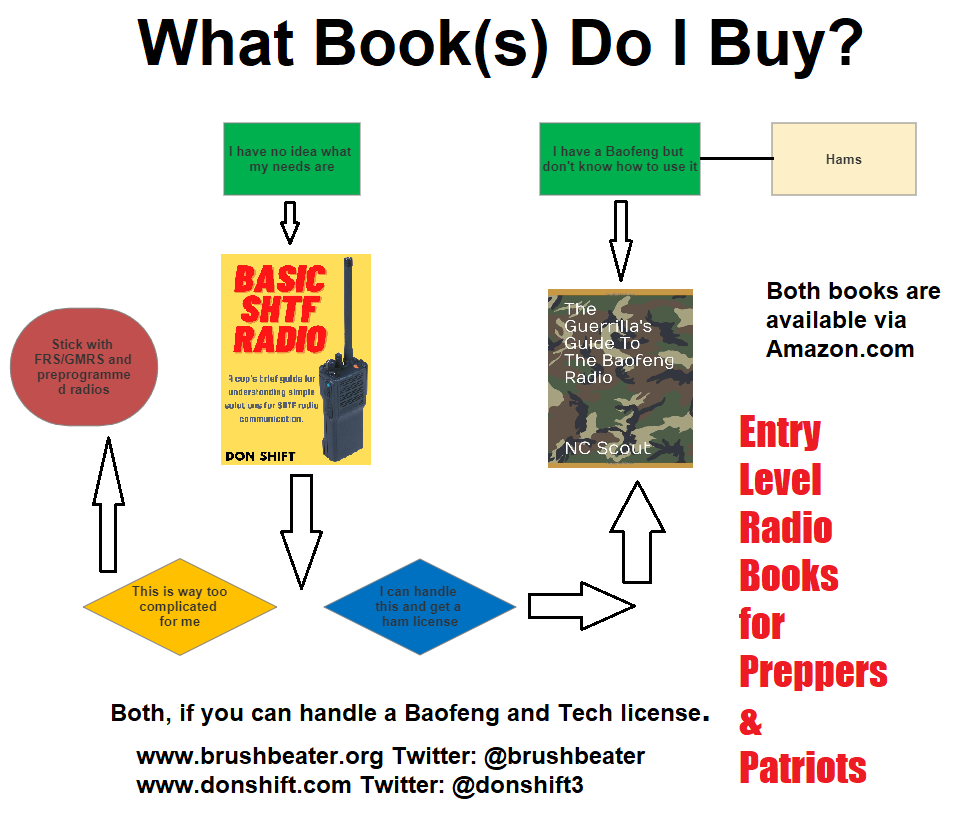

If you are totally bewildered and confused by ham radio and what options you have, start with my Basic SHTF Radio. This is a guide to let you know what your options are (if ham is too much for you, GMRS & FRS are great, easy options with a lot of close similarity to UHF ham that will work right out of the box). I consider this next one to be the companion and "Intermediate SHTF Radio" to my basic book. Brushbeater, aka NC Scout, who runs an excellent radio course by all reports, has published his guide to using a Baofeng radio: The Guerrilla's Guide To The Baofeng Radio. If you have a Baofeng and kinda understand the basic of radio and what your needs are, or if you have a new Tech ham (amateur operator) license and need to figure the stupid thing out, start here. Also check out Scout's classes at Brushbeater.org.

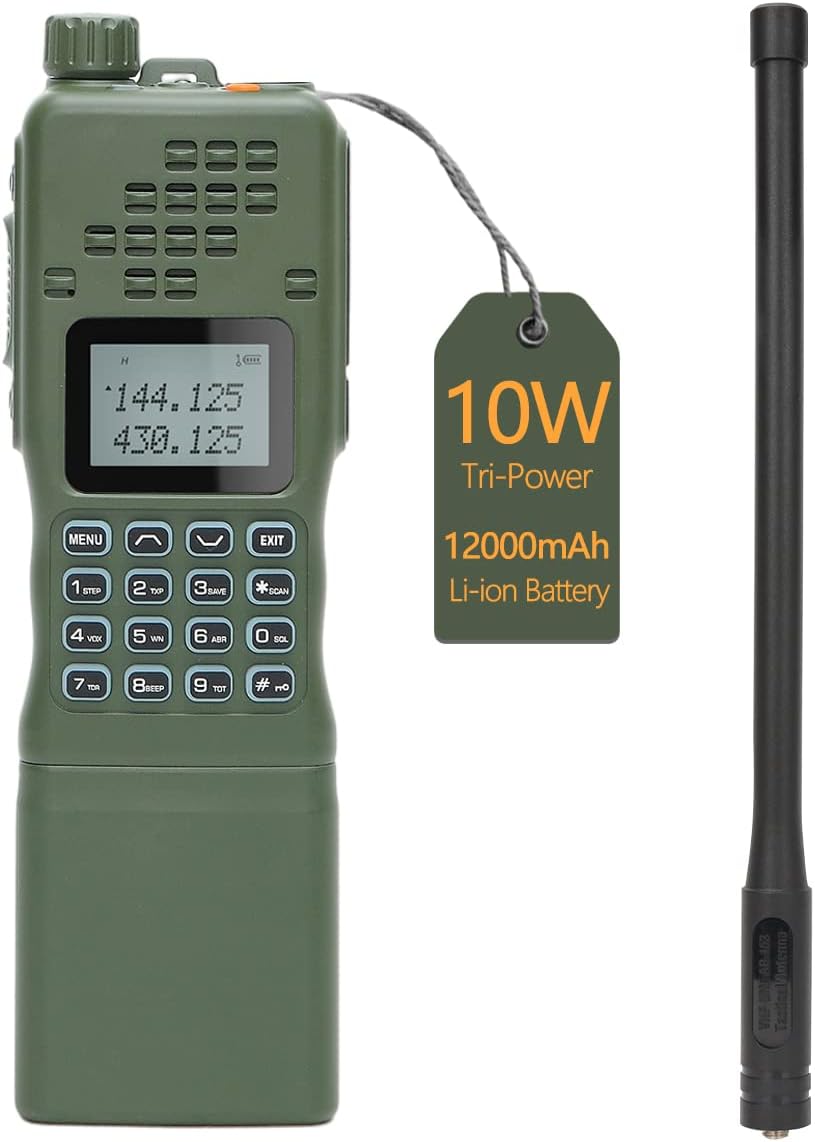

Have you thought about how you will communicate if the cell network goes down? The modern telecommunication system can be taken down through cyberwarfare, hackers, or a natural disaster. Cell towers only have a limited amount of fuel in their generators to keep running after a power outage. The regular telephone system is resilient but is now more than ever dependent on the Internet to facilitate calls. Do not rely on cell phones. Cell networks can be easily overloaded in large emergencies. Anyone in earthquake country can tell you even the old phone system was overloaded after a quake. You picked up and waited for a dial tone. Crowded areas often get very poor cell reception because there is too much traffic for the node to handle. We’ve all learned one way or another that the cell network capacity can be stretched and broken. For me this was one Black Friday morning when tens of thousands of people descended upon our outlet mall. From a disaster, to a power outage, to simply having more phones in small area than the local cell nodes can handle, you cannot rely on a cell phone. A long-term power outage from a disaster is one thing; the towers should still be intact. In an insurrection or major social upheaval of some sort, cell towers may be shut down entirely. A disaster may render the cellular network impotent, such as if the backup generators eventually run out of fuel. A major regional disaster coupled with a fuel shortage may cause this. A cyberattack may just disrupt cell traffic until the attack is over. Outside events like EMP, nuclear war, or loss of satellite communications/GPS may render the modern cell networks into junk. A war with China or Russia would also probably see major infrastructure hacking and even damage to the GPS system or satellite communications, which would wreck cell towers’ ability to connect with one another. Sat phones aren’t an answer either; just imagine a war where satellites are deliberately targeted. Robust forms of communications are necessary for your family, information gathering, and tactical self-defense use. This leaves us with radios. For those unwilling to foray into ham radio, there are some easy options that don’t rely on cellular towers. RadiosRadios are good when you need immediate communication at the push of a button. You aren’t texting in a gunfight and dialing a call is too long. Also everyone on your team can hear a radio transmission. Radios will be the primary form of communication in a major grid-down type of disaster. The downside to radio is that in the forms that you will likely have access to, there is zero privacy, all frequencies are shared, and are short range. Remember to replace that cheap, short “rubber ducky” antenna on your radios and scanners with taller, high gain ones. For tactical use, folding flexible antennas exist. Most radios will come with a cheap, six to nine inch “rubber duck” antenna, their length often 1/8th of the frequency at that wavelength. This should be immediately replaced with a longer antenna. For common VHF/UHF radios, this will be around a 19” antenna. Flexible and folding antennas exist for easy storage, mounting in a belt holster, or on load bearing equipment. Unlicensed optionsOur discussion will be limited to bands that do not require an amateur operator’s (ham) license. If you plan on using anything other than simple, pre-programmed radios in the neighborhood, do some serious research. You don’t need to necessarily get a license for all of these options but do learn how the various bands work in the application you want to use. Learn what equipment works best and how to install and program it. Use your Google Fu! I recommend a home GMRS watt base station and at least one car with a 50 watt mobile radio. This would replace a cell phone when driving around town when the grid is down. Each family member would have a GMRS walkie-talkie; the older folks would get the more expensive models with longer antennas and the kids would get the bubble pack ones when they go play down the street. To talk to friends or relatives across the county, this would be done with a CB radio mounted on the house. GMRS: General Mobile Radio Service. Technically this requires a license that applies to you and your family, but because it requires no test and is approved automatically, it could be considered unlicensed. Since most users don’t have licenses and there is no enforcement, it practically is unlicensed. GMRS is used for family communications, popular with off-roaders, often used without a license (illegally) by anyone needing a short-range radio. The license is $70 as of this writing, supposedly to be lowered to $35 later in 2021. The license is good for 10 years and practically any close relative can use your license. I have not heard of the FCC prosecuting unlicensed use. You can install repeaters and use radios up to 50 watts. This is a poor-man’s UHF ham analogue, but lots of people are using few channels, so you have less options. Portable radios are usually 5 watts, which will give you 1-3 miles in town without connecting to a rooftop antenna. Mobile (vehicle) radios and a rooftop antenna could cover up to 15 miles depending on the terrain. FRS: Family Radio Service. Basically your cheap blister pack radio. Only good for talking within a few blocks, like one end of the street to the other mostly. Though the frequencies and possibly the radio would have greater capabilities, you can’t replace the crappy antenna. CB radio: Citizen’s Band radio falls at the high end of the HF spectrum. CBs are right on the border between “long range” HF/High Frequency and “short range” VHF/Very High Frequency. Maximum legal wattage is 4 watts, which won’t reach far, but if you buy illegal amplifiers, you can increase power dramatically to reach across whole counties, depending on the terrain. Under the right conditions and with the right equipment, a CB radio base station could reach out around 30 miles or so, giving you medium range communications without a repeater. I recommend a home GMRS watt base station and at least one car with a 50 watt mobile radio. This would replace a cell phone when driving around town when the grid is down. Each family member would have a GMRS walkie-talkie; the older folks would get the more expensive models with longer antennas and the kids would get the bubble pack ones when they go play down the street. To talk to friends or relatives across the county, this would be done with a CB radio mounted on the house. If you would like greater flexibility and the benefits of better radios and frequency choices, pursue your amateur license. The material for a Technician license isn’t overly complicated and study guides provide a good introduction to the test material. Studying for the test can be done by simply memorizing the question pool. Knowledge of Morse code is no longer required. Don’t let the study material and test throw you off; once you pass, for most entry-level radio usage the knowledge is practical versus technical. Ham (licensed options)Ham radios require an amateur operators license. The test is easy if you study (memorize the answers) and gives you far more frequencies to use. Those who have looked into ham radio know about UHF/VHF and shortwave radio, but one band goes overlooked. This one band might make a difference. UHF: Usually in the 400 MHz range and often found in the non-ham radios commonly available in stores (GMRS and FRS). For hams, this includes the 70cm AKA 440 MHz band (Technician-level amateur operator license required at minimum). This is for short range (<5 miles) communication. VHF: Usually in the 30-200 MHz range for civilian radios. This is most common for 2m band (144-148 MHz) ham radios, like the ever popular Baofeng radio. The 2m band requires at least a Technician-level amateur operator license at minimum. This is for short range (<5 miles) communication. 1.25m Most ham and consumer radios operate in the 2m VHF (140 MHz) and 70cm UHF (440 MHz) bands. These are the most popular FM frequencies because most cheap radios (Baofengs) utilize them. I personally would recommend 1.25m (220 MHz) because it’s so similar to 2m (140 MHz) VHF, but with a lower noise floor. 1.25m is not widely used and none to very few commercially available radio scanners are tuned for these frequencies. Because few people have these radios and it’s highly unlikely any civilian will have a scanner that can pick up this band, there is a low, but not zero, probability of intercept. Baofeng sells 1.25m handsets and a variety of mobile and rack units are available. Be aware that your communications are not secure. They are less susceptible to intercept than other frequencies simply because there is a lesser chance that someone is listening. These are not secure channels but are the equivalent of having a private conversation in an empty room with the door open. Learn more, buy my book.If this is "old hat" to you, skip to my good online friend NC Scout's "The Guerilla's Guide to the Baofeng Radio."

|

Author Don ShiftDon Shift is a veteran of the Ventura County Sheriff's Office and avid fan of post-apocalyptic literature and film who has pushed a black and white for a mile or two. He is a student of disasters, history, and current events. Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed