|

Author’s note: the accounts mentioned in this article are taken from Falkland Islanders at War by Graham Bound (2006), published by Pen & Sword Military.

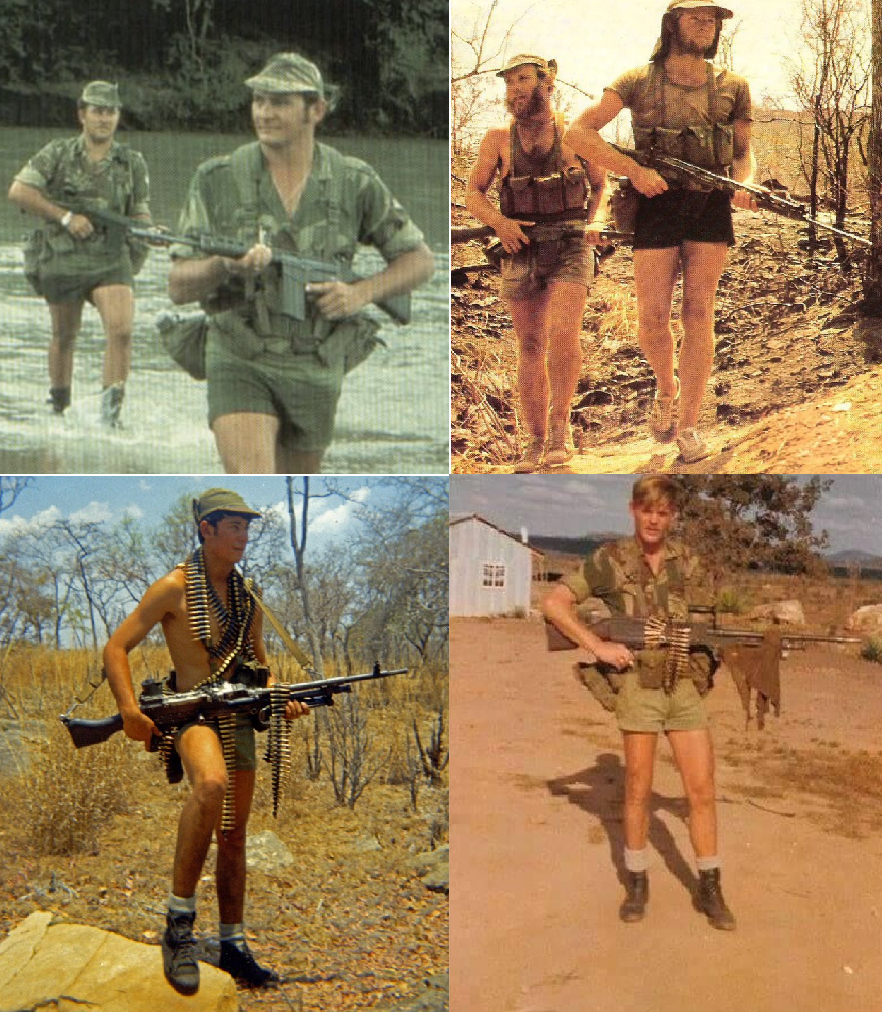

Imagine you live in a remote, small community that is invaded one day by a vastly superior military power to the local token military/militia forces. How would you communicate with your neighbors or your own military? How would you gather and send intelligence? What tricks could you play with ham radio? In 1982, for the residents of a remote British colony, this was no thought exercise. Far south in the Atlantic, off the eastern tip of South America, sits the rocky, windswept Falkland Islands. Half the world away from Great Britain, this little outpost of Albion was the subject of a brief, nasty war in 1982 when Argentina invaded what they call (and claim) “Islas Malvinas.” Make no mistake; as trivial was this footnote in history may have seemed on the news, it was a real war with ferocious fighting, heroism, and daring risks taken by the islanders. The Falklands had been little more than an outpost for the wool trade and a stopover for ships since Britan colonized the islands in the 1830s, following a brief attempt at settlement from Argentina that was abandoned. Despite the islands having little to no strategic value, these treeless islands that resembled Scotland were in a natural position for neighboring Argentina to claim them. In the decades leading up to the war, the UK and Argentina had tried various means of rapprochement over the islands. In an era of decolonization it really did seem like Whitehall wanted to give the territory over to Argentina. One could almost call the islands neglected by their motherland where, at the time, the almost entirely British-heritage population was denied full British citizenship. Despite all this, the islanders felt themselves to be British, even those whose families left the UK generations ago. No islander wanted to be handed over to Argentina like a dirty memory of the colonial past only to be under the heel of a military dictatorship. The green-eyed suitor was decidedly a worse choice than the inattentive UK. Argentina was currently governed by a military coup known as the Junta in the years following its Dirty War against what we would call progressivism. It is argued with much merit that the war was launched as a distraction against public dissatisfaction with the Junta’s repression and economic policies. While readers may sympathize with the Junta’s heavy hand against socialist forces at home (throwing communists out of helicopters), the totalitarian tactics bled into the occupation force’s behavior towards the civilians islanders. Thankfully, aside from some selected abuses, the invaders remained fairly well restrained towards the “kelpers” who endured the two-and-half month war. However, the suspicion, and treatment, of civilians was harsh but thankfully not deadly. Death for the islanders who resisted would have been an easy stretch for Argentina. However, reprisals of this type were nil. Knowing that the small detachment of Royal Marines, about 40 (as a troop exchange was happening at that time), and small Defense Force would be overwhelmingly outnumbered, Governor Rex Hunt ordered that there be no guerilla warfare. The help the islanders did provide through intelligence gathering, minor sabotage, and scouting was invaluable to the British task force. This article looks at the use of radios by civilians. The accounts highlight the risk of radio operation in a non-permissive environment. There were many intrepid islanders who, at great risk to themselves, passed intelligence back to Britain and even interfered with Argentine communications. Radio is a powerful tool of resistance and some plucky kelpers used it to good effect. Radio communication was, and still is, a way of life in the Falklands. The islands consist of one major settlement (Stanley), numerous hamlets, and isolated sheep farms across approximately 4,000 square miles of the two main land masses. Especially in the 1980s, communication was largely by radio as the telephone exchange only worked in the city. 2-meter radio formed the backbone of the “bush telegraph” communication system as their form of citizen’s band radio. Many islanders also had high-frequency (HF) radio sets to communicate over longer distances, with ships, and to the outside world. Families owned multiple VHF radios. Sets were in every vehicle. Longer-ranged sets provided communication across the craggy islands and even across the world. Total confiscation, even with registration, would never be possible due to their prevalence, proliferation, necessity, and the huge distance required to reach remote settlements. The Argentine occupation government realized this and allowed rural radios mainly for the purpose of radio consultation with doctors during their regular “radio surgery.” The islands’ radio operators were apparently all licensed. In such a small place, although enforcement probably was not much of a concern, unlicensed transmission would be obvious among such a tiny population. Records of operators’ licenses were kept at the Post Office which meant that once the islands fell to the Argentines, intelligence officers seized these records. Immediately the security officials knew not only who was licensed but the particulars of their equipment. At once, we see the problem of government registration and licensing; it is a roadmap for confiscation and harassment. Americans tend to think in terms of firearms but the same problems we fear over guns the islanders faced with radios. Sad Hams delight in government approval and tracking, but its easy to see how gatekeeping can be a liability during exigencies. Once the order to turn in radio sets was broadcast via the local commercial radio station, it would be easy for military police to raid the homes of those who failed to comply with the order. House-to-house searches to check compliance and even searches for clandestine transmitters was commonplace throughout the war. The level of fear of illicit transmissions the Argentines had belied the actual level of spying that went on, at least up until the final counter-assault. While Sad Hams are proud that they are registered with the government, such behavior can be a double-edged sword. Americans may not face the same prospects of invasion as the islanders did, but one can imagine how a registry could be used inappropriately. One benefit to the American scheme in combination with the advance of modern technology is that individual equipment is not registered and it is quite affordable to have separate radio sets, particular dual-band VHF/UHF sets like the Baofeng. Unaccounted for sets are a buffer against confiscation, which one fortunate islander used to his advantage. Lighthouse keeper Reginald Silvey, shortly after the invasion began, made a contact on the 15m band and passed a simple message to his relatives through an English ham 7,800 miles away. What began as a desperate dispatch to family, turned into the passing of actual intelligence to British defense authorities, requiring a cat-and-mouse game to outfox the Argentinian communications specialists. Ostensibly, Silvey complied with the military orders and surrendered his transceiver. Silvey turned in his registered radio and made “a fuss” when handing it in. He intended to make it memorable so to remove any suspicion that he had a transceiver. Additionally, he tore down his large antenna. During the dismantling process, a helicopter flew by and he and his friend were sure to wave to make sure the work was noticed. To get around the problem of radio confiscation, he turned to his friend George. George captained a small ship and his HF radio had not been taken out of his ship. He retrieved it in secret, using a subterfuge to access the restricted waterfront, and smuggled it into a hiding place for Silvey to receive. Should the Argentinians notice the radio was missing from its place on the ship’s bridge, George would claim that while the ship was unattended, soldiers stole it—an entirely plausible answer. Two problems now confronted Silvey; a power supply and an antenna. For the former, he turned other friends who drove hospital Land Rovers. A 12-volt battery was delivered that would provide power for the rest of the war. For an antenna, the steel clothesline made do, although it was not ideally matched to the frequency. Argentine troops still raided homes on a daily basis which meant Silvey was at risk. A pass issued by the commanding general, Mendez, served to notify troops that the house had been cleared and that they should not enter, although this was not an ironclad guarantee. Silvey, now back on the air, made contact with a Briton who passed intelligence on to the Ministry of Defense. From his window, the lighthouse keeper could see the airport and wanted the authorities to know that the area, packed with troops and supplies, could be attacked without harming civilians. Following messages contained counts of weapon emplacements and their locations. One important bit of info passed on was the presence of a surface-to-air missile (SAM) launcher near the airport. The authoritarian military occupation forces were quite serious about stopping illicit radio transmissions although their reach exceeded their grasp. Direction-finding vans combed the only city and capitol of Stanley as well as the rural portions of the island, known as the “camp.” Aiding his evasion of the foxhunters, Silvey used terrain against the Argentinians. Despite some islanders who were very remote from the bulk of the troops in town, Silvey sat on Cape Pembroke only five miles away. However, terrain, propagation physics, and human nature were somewhat in his favor. First of all, the Argentinians were focused mainly on short-range VHF (2m) transmissions as this was the most common form of radio used in the islands. A major concern was local communicating with missing Royal Marines or SAS/SBS commandoes landed on the island to conduct reconnaissance. Hence the focus was less on high-frequency (HF) radio. Direction finding (triangulation) of radio signals is affected by terrain, which can block both the propagation of transmitted signals and inhibit reception. Stanley is sited on the slope of a hill above a bay, which would place it below Silvey’s radio horizon (and that of much of the island). Putting terrain features between the transmitter and an interceptor can be an effective tactic, depending on the antenna, the band’s propagation characteristics, and other factors. HF signals, being subject to ionospheric variations and skywave propagation, may exhibit non-linear paths and inconsistent signal strengths over different paths. This can introduce errors and uncertainties in triangulation calculations, making it more challenging to precisely determine the source location. On the other hand, VHF signals' line-of-sight propagation provides more predictable and direct paths, allowing for more accurate signal source triangulation. Signal source triangulation requires the use of multiple receivers to measure the signal arrival times and calculate the intersection point of the signal paths. While the propagation characteristics play a significant role, other factors like receiver accuracy, timing synchronization, and environmental conditions also influence the overall accuracy of the triangulation process. Hence at least two mobile vans would be required to narrow down the suspected transmission location for house-to-house searches. Silvey transmitted using a mixture of voice and morse code. His signals were often sent “in the blind”, that is transmitting without first establishing that someone is actually receiving. GCHQ, the UK’s version of the NSA, with their incredible global radio signal detection capabilities, likely detected these signals once they were aware Silvey was passing transmissions. He also kept his transmissions short (around 15 seconds), which aided being able to evade detection. Longer transmissions give the direction-finders more time to detect and triangulate the signal (lowering the signal strength and using directional antennas, in line-of-sight bands, also decrease the probability of interception). Other islanders reported good results by decreasing their transmitting power to limit the propagation of their signals, thus preventing the distant interception sites/vans from receiving them. Understandably, the Argentines were paranoid about British commandoes spying. Signals were detected, or believed to have been detected, in town by the Argentine foxhunters. However, no actual source was ever found. The area of interest for the electronics crew was some distance from where Silvey was transmitting from. While it is possible that others were transmitting, this information has not been revealed. Several islanders did mention mysterious British men who seemed out of place moving about the town in the later phases of the occupation. As the Paras and the Royal Marines advanced, these mysterious men even made contact with particular islanders apparently making sure that they had not been arrested or killed. Many are certain these were British intelligence officers or commandoes. If MI6 or the armed forces infiltrated spies into Stanley prior to the British counter-invasion, it is still classified. Another tactic Silvey employed was the use of another islander’s call sign, that of Bob McLeod, who lived across East Falkland in the small community of Goose Green. Silvey would drop Bob’s name, well known among hams who sought to make contact with the coveted, remote VP8 callsign. This bit of deliberate misinformation would lead any potential interceptors to assume McLeod was transmitting, which would be impossible since his radio had already been confiscated and himself interned. To this day, this “disinfo” had led people to believe in the legend of “Radio Bob.” In a separate incident, after the residents of Goose Green had been interned, Argentinian troops occupying McLeod’s home came across a photo of him in uniform. McLeod was a member of the Falkland Islands Defense Force, the island militia. Already suspect for being a licensed ham, the occupiers accused him of being a spy. Much pleading had to be done on Bob’s behalf to convince the troops that his radio had already been impounded and he had been confined with everyone else. This the troops should have known, but the Argentinians did not send their best, and many such incidents involving the hair-trigger and largely conscript soldiers occurred. Even if the information provided was not helpful, the continued transmissions forced the Argentines to monitor and hunt civilian radios. This dissipated their efforts which might otherwise have been focused on searching for special forces radioing back to the task force. Even the house-to-house searches that followed ensured that the population remained hostile to the occupiers. A Chilean immigrant, Mario Zuvic, who hated Argentina devised a concealed aerial in a treetop that he and his friends used to listen to Argentinian forward observers on nearby hills. Some of the traffic they intercepted was mundane. Argentinians would be phone patched via radio back to their families. This was the only link, aside from mail, that the mostly conscript army of little more than boys, had with home. Other efforts were considerably more dangerous. Despite all of the interference and the incredible frustration it caused, Mario’s transmitter was never found. In the rolling terrain of the “camp”, it wouldn’t be easy to triangulate the signal. Mario and his friends would send false signals to the occupiers’ radio control center including fake orders to disrupt forward observers. In addition to this, they scanned the airwaves until they detected Argentine radio traffic then jammed the conversation by transmitting at maximum power. After one of the British landing ships was attacked, the following day when it seemed like it would happen again, Mario jammed the frequencies by simply keying the mic. This left the occupiers unable to send messages to their headquarters all day and probably disrupted both attacks on the ships and other combat operations. Not long after an auxiliary airbase was completed at Goose Green, it was attacked by Harriers. Though the anti-air defenses scored one kill, the uneducated troops insisted that there was a spy among the civilians passing radio traffic to the British task force. This resulted in a house-to-house search for the radio that didn’t exist. One little girl even asked her father “Daddy, are we going to be shot?” It is questionable whether or not the Argentines would have executed anyone. Given the lack of physical resistance in the islands and the rather hopeless position the occupying forces were in, it seems unlikely. General Menendez said that anyone caught transmitting intelligence to the British “would have been considered a spy and that that traditional treatment of spies” (being shot) would have been applied. Perhaps if Britain had not moved to recover the islands or if there was an active resistance taking Argentine lives the clandestine radio operators would have been treated more harshly. Even so, Argentinians committed many war crimes, generally conducting or threatening mock executions. One captive civilian in Goose Green tuned a radio to the BBC, but in doing so, came across a conversation between hams. The troops thought that the islanders were somehow communicating with British forces and cocked their weapons threateningly. Eventually the occupation government’s sympathetic civilian administrator intervened and managed to get a senior military officer to parole the men to a hotel. After an incident where an islander attempted to contact the British flotilla, helicopters were loaded with men and radios then flown back to Stanley. At the police station, one man was forced to write a statement and threatened with a knife. Others were taken outside, ordered to dig a trench (presumably) a grave, then forced to kneel in wet grass before soldiers dry-fired pistols in their backs. The brave acts of the islanders during the Falklands War shows that radio is an important tool not only for communication, but for passive resistance. We won’t know for a few more decades what impact the passed intelligence had (until it is declassified) but even if it was redundant, much effort and time was expended by the occupiers trying to counter it. Civilian radios do have a place in creating electronic warfare as long as it is done smartly. And finally, to the consternation of Sad Hams everywhere, registration and licensing leads to confiscation. Always have radios no one knows about hidden away. If this topic intrigued you, also check out NC Scout’s book The Guerrilla's Guide To The Baofeng Radio. Bare-legged Rhodesian soldiers have become a meme among certain segments of the Internet. Some like the look, others, like Tactical Wisdom-series author and Marine Joe Dolio call them a major health hazard in combat/SHTF. Joe doesn’t actually hate cargo shorts, but he considers them a liability and vector for injuries/infections in combat. I agree. I’ve hiked through rough terrain in shorts and have torn my legs up badly. My father came very close to a potentially life-threatening illness due to wearing shorts in inappropriate conditions. Do you really want to go prone on jagged rubble with unwashed skin that’s been going through an apocalyptic hellscape? I’ve suffered from whatever the western version of chiggers are twice and I can’t imagine how much worse a staph infection could be. While Rhodie-style shorts may make for good morale and propaganda, they do pose a serious concern for injuries and infection. Joe emphasizes a focus on basic first aid, not to detract from traumatic injuries, but because the focus on treating “minor” wounds early has been lost—we’ll see later why that’s important. A small cut we might brush off today in a relatively clean garage could be a nick in the field that easily festers and becomes deadly in SHTF. Prepping author and Siege of Sarajevo survivor SELCO reported that unwashed clothing became a similar vector for infection. People who hadn’t bathed or laundered their clothing for months carried high bacterial loads on their skin and in the fabric. Wounds would then almost be guaranteed to get infected. Remember that the environment was grid-down, so there was no proper plumbing or sanitation. But let’s talk a little bit about those men in the ‘70s with short shorts before we go any further. For those who don’t know, Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) fought a war against communist-sponsored black guerilla-terrorists who were attempting to overthrow the white majority government. The white government knew what a s—t show would result if black communists took over (see the history of Zimbabwe and Robert Mugabe). Western economic sanctions over segregation and the unilateral declaration of independence from Britain lead to the state becoming a pariah. Despite the political troubles, the beleaguered Rhodesian army was effective and legendary. The photo of a patrol crossing a river in shorts, brushstroke camo, and with FN FALs carried at the ready has become an iconic image of the war. African terrorists had names for Rhodesian troopers like “ghosts with white legs.” Short-pants among Commonwealth soldiers in the mid-20th century was not an unusual bit of kit. While not issued to troopers, the classic brushstroke shorts were often made out of standard camo pants. But why shorts? The only cool factor was temperature wise, the plague of Instagram not being a thing yet. Comfort appears to be the number one issue due to the high temperatures. For example, Selous Scout often wore “trainers” (sneakers/tennis shoes) instead of boots. In fact, some paratroopers chose not to wear ankle-high boots when jumping, arguing that the actual rate of injuries was low. Shoes were more comfortable and easier to be stealthy in. Comfort being the number one issue, some reported ancillary benefits from shorts even with the potentially injurious flora and upon human behavior. A hunter with experience in Africa reported that long pants were caught by thorny plants. This caused delays and noise, so he preferred to accept the scratches. The theory on thorns is that although they do cause scrapes, they do not become entangled in skin as they would with cloth. He was not alone in this opinion. A Selous Scout officer once said the inherent danger of shorts in the bush enforced stealth and caution. Quick, rash movements not only made a lot of noise but would result in injuries. Training of course is best but risking a gash in the leg apparently reinforced care in walking. Seems a bit like the reasoning behind the three-round burst on the M16A2, eh? As the Scouts transitioned away from primarily tracking to more anti-terrorism and direct action roles, the shorts were replaced in the field by pants. Rhodesian “troopies” took pride in minimalism and toughness, so this may have been a factor in the popularity of shorts beyond comfort. Yet all good things must come to an end. In 1977, shorts were forbidden for the Rhodesian Light Infantry (RLI) on operations. Sources report that this was largely obeyed, unlike the above boots order. I spoke with Civil Defense Manual author Jack Lawson, himself a veteran American volunteer, who confirmed the transition at least in practice, if not by command. However, it was green shorts that faded to a bluish color in the sun, not camo. A transition was made to jumpsuits and Lawson transitioned away from “the naked body” style of uniform due to hypothermia in early morning helicopter rides (G-Cars). But are shorts a good idea to wear in combat or SHTF? Probably not, although the Rhodesian reasons for wearing them initially, were not slapdash ideas. Shorts aren’t terrible things to wear; I prefer them when doing general outdoor activities because of greater airflow to my bits, hence less sweat, and greater cooling due to my exposed legs. On the other hand, I often trample through the “bush”; creosote, Manzanita, and sagebrush. I have scars from cutting my legs on stuff. Snakebites are a constant concern, although I’ve only ever encountered a rattler twice (knock on wood). Once I came back from a hiking vacation and my young niece got worried I’d seriously hurt myself due to the amount of minor wounds I got from a particularly nasty off-trail bit. I looked pretty rough. Recently I learned my dad has had some serious health problems. Chronic cellulitis had come very close to turning septic and gangrenous. It was so bad he wouldn’t let me visit because he was afraid his legs were literally rotting away like an unmanaged diabetic. A hospital stay and nuke-it-from-orbit levels of IV antibiotics later, he’s finally on the mend. He’s feeling better, optimistic for the first time in a while, and expected to make a full recovery. Why did this happen? He lives in a very humid area on a rural piece of property where his main hobby is landscaping. Unfortunately, part of the land is a swamp infested with blackberry vines. Working in thick brush and thorny vines cut his unprotected skin up, allowing infections and weird stuff to go on in his legs. Like a typical man, he did not get this stuff properly treated until it was bad. Of course, proper medical care early on would have stopped it from getting as bad as it did. However, in a civil war/SHTF there is likely to be very poor to no medical care. High doses of mega-antibiotics will be a rare thing, so injuries are to be avoided. Infection has probably caused more fatalities in wars than actual battle. Untreated infections with austere conditions with all sorts of unknown contaminants can cause huge problems. In my dad’s case it was just cow dung and general Pacific Northwest waterborne contaminants. Post-SHTF, it could be major diseases, including “exotic” ones imported by the foreigners pouring across our undefended southern border. Imagine going prone on a rocky surface in a firefight and surviving unscathed, aside from a bloody abrasion to the knee, only to die in a few weeks from septic shock. Apart from the Commonwealth, operational use of shorts seems to be slim or exceptional. Kris “Tanto” Paronto, wore shorts during the fight in Benghazi because “If I was going to fight, I was going to fight comfortable.” One interesting contrast in protection is the Brazilian Army’s Caatinga troops. The Caatinga is a semi-arid desert filled with spiny and thorny plants, not unlike the Sonoran desert of southern Arizona. This unique military unit wears tough, full-bodied denim uniforms reinforced with leather complete with gloves. Shorts may feel comfortable up to a point, but if it’s too hot, like over 100°, exposed skin is letting the heat in. If you visit Las Vegas or Phoenix, you’ll notice police officers wearing full length sleeves even in 115° heat. Yes, sunscreen has reduced the need for covering the skin in the summer sun, but heat control is more important in very high temperatures. One could always compromise (especially if there is a breeze) by wearing lightweight, but long sleeves. As for sun protection, will you have the ability to apply sunscreen in combat conditions, especially where sweat and water crossings may wash it away? I chose to wear a campaign hat on patrol because if I was going to be outside for a long time, such as doing traffic control, I wouldn’t be able to apply SPF 50 (over my SPF 15 lotion I put on in the morning after shaving). Also, the scent of sunscreen is highly distinctive and could give away a concealed fighter to an astute tracker. Unfortunately for the guys who want to look stylish by channeling their inner “troopie,” shorts are contraindicated in SHTF. You’ll stand out and your white legs will give you away in the underbrush—are you really gonna camo stick your legs or rely on getting a nice, dark tan? White skin can be highly reflective, camouflaged or not. The dangers of insect bites/stings, thorny plants, scrapes, cuts, and sunburn aren’t worth it. A grid-down world or one where you can’t just go to a hospital will result in minor infections becoming major, life-threatening ones. Save the brushstroke nut-huggers for the barbecue and wear some pants. Joe Dolio’s Tactical Wisdom series is a set of manuals that far surpass what the average US military field manual has to offer. His upcoming TW-5 will include a section on first aid. Visit his website at www.tactical-wisdom.com and follow him on Twitter @dolioj.

Don Shift is a veteran of the Ventura County Sheriff's Office and an avid fan of post-apocalyptic literature and film. He is a student of disasters, history, current events, and holds several FEMA emergency management certifications. Visit www.donshift.com and consider supporting him by buying his book Rural Home Defense, which includes a chapter on lessons learned from the Rhodesian Bush War. Mistakes made by settlers

Discussion Settlers did not set themselves up for success. Their farms/ranches were isolated, in poor defensive locations, had few capable defenders, and situational awareness sucked. If your house is in a poor physical defensive position (or design), you have to overcome this with technology or manpower. Remember that barricades and obstacles can only delay an attack; manpower can defeat an enemy and turn that obstacle into a force multiplier. More men allows for more area to be defended and casualties to be absorbed. Lastly, if you aren’t paying attention and get surprised you’ve lost the advantage. I get that everybody wants their own land and that scarcity of resources like grazing land and water made it necessary to spread out, but it was stupid from a defensive standpoint. Houses that were widely separated could not rely on each other for mutual support. Given that many of these frontier families were a nuclear family with one adult male, maybe some older boys, there wasn’t the manpower to defend them. When help was needed, anyone who could escape and manage to evade the Indians faced a desperate run, ride, or walk to neighbors that could be miles away. Even a one mile jog might take 10 minutes for someone in average shape. Up to half an hour might pass before help arrives and God only knows what horrors may have transpired in the balance. The houses should have been built much closer to each other, like 100-200 yards maximum; an easy rifle shot. With a clear view, each house could offer supporting fire to the others. Neighbors would be in close proximity for refuge and defense. More eyes could more easily keep watch. Modern building practices where homes are on smaller lots now naturally accommodate this kind of thing, though the homes weren’t laid out and built to maximize defensive fire. Today, homeowners will probably have to clear brush and trees to improve sightlines for natural surveillance and for supporting angles of fire. Radio communication and cameras can supplement human lookouts. Vehicles conquer the tyranny of distance. Technology and development patterns change some of the risks, but there are plenty of rural properties that are just as isolated and undermanned as in the frontier days. One repeatedly losing tactic was for a settler to chase after raiders by himself. Pursuing Indians alone or in pairs was a recipe for disaster as the Indians almost always outnumbered the settlers. In many cases “Pa” was ambushed or routed and killed when he went rushing off alone to recover the stolen horses or try to get some parting shots in. If the family was lucky, they were able to defend alone from inside but often the house fell anyway. It might seem natural to try and recover a stolen vehicle or livestock as the enemy flees, but this is like swimming out into shark infested waters. As you leave the house, you deprive it of a capable defender, lose the benefit of any defensive works (fencing/covered positions), and are more easily flanked by the enemy. Going out alone is stupid. A smart enemy who is being pursued would setup a hasty ambush or just circle back and engage their pursuer. Perhaps they were content to “live and let live” until you decided to chase after them. Too many victims of robberies, etc. have been killed because they decided to go after their attacker, usually unarmed. If you are in a weak position, don’t do things that make yourself more vulnerable. You could be running into a trap. You cannot afford to let ego or revenge blind you to tactical realities. If your family is alone, if the enemies are withdrawing, and if you are outnumbered, let them go. I understand that things might be different if a family member is kidnapped, but act smartly. In today’s world, a vehicle could be identified or followed from a distance while you radio for help. There may be moments of necessary self-sacrifice, like if a family member is a captive, but don’t potentially sacrifice your life for “stuff.” Tips for today

This article is a part of my new non-fiction book, Rural Home Defense: A cop's guide to protecting your rural home or property during riots, civil war, or SHTF.

Note: Many of the individual accounts this analysis is based on are taken from the raids of the Comanche and Kiowa tribes and the observations made from them (and others) generalized. See also my book Rural Home Defense. Rural homes in SHTF will suffer from isolation and potentially lack of communication. A situation not unlike that of homesteads that fell to Indians in (mainly) the 19th century will be faced by many rural properties. Rapid raids, not by horse but by vehicle, by criminals and not natives, will share some overlapping elements of what our frontier ancestors faced. I believe that Native American warfare on our frontier is a better idea of what rural Americans will face post-SHTF than Rhodesians did during the 1970s Bush War. Both the Zimbabwean communist terrorists and the Native American tribes fought guerilla wars; one successfully and the other unsuccessfully. The Indian population was small and easily reduced by warfare, famine, and disease. In Rhodesia, the European population was outnumbered by the Africans and white population flight eventually doomed the minority government. All the African guerillas had to do was bide their time and keep the pressure up. Native Americans were fighting a losing war against a technologically and numerically superior enemy and could only inflict painful stings. When Indians couldn’t win a decisive engagement over the Army, they sought to hinder, delay, and demoralize the soldiers the best they could. Undefended homesteads were easier to wipe out than a cavalry troop. Atrocities perpetrated upon pioneers had the effect of frightening and driving some of them away. The population imbalance was always in the settlers’ favor so no matter how brutal the Indians were, they couldn’t out kill the overflowing European population. Raids sought to steal goods for material gain and were conducted by small groups. This would in turn have the effect of requiring taking revenge on the raiding tribe, which could spawn open warfare. War parties would go out with the objective to kill and take captives to avenge wrongs. Many engagements were blood feuds intended to avenge the death of relatives or tribe members. This tended to produce a never-ending conflict that was self-perpetuating as each new retaliation must be punished. Modern criminals will target properties for hit-and-run attacks to gather supplies or valuables. The “Indians” may be desperate criminals coming out of big cities or roving groups of bandits. If political or racial strife is interjected into a struggle for resources, atrocities to shock and demoralize may be perpetrated on victims. We have seen inter-tribal warfare in many countries get very ugly. Whether it is Native Americans vs. pioneer Americans or ISIS vs. the Kurds, awful things done to “others” is an ugly part of human nature. Wagon trains Wagons traveling alone was a bad idea. Indians deliberately separated parties or took advantage of separation to more easily kill or capture their victims. Trains of wagons provided additional security, more provisions in case some were lost/spoiled, and help should anyone get stuck or find some other kind of trouble. Wagon trains had mounted advance and rear guards who scouted for Indian ambushes. Wayward trains would blunder over the horizon without the use of scouts riding ahead or on the flanks to look for signs of approaching Indians. The Indians could surely see and hear the wagons long before the opposite occurred. Failure to scout resulted in ambushes. Scouts also had the duty of looking for a suitable and defensible campsite. When setting up camp, doing so in the bend of a river was recommended as the water would form a defensive perimeter on roughly three sides. Areas with dense brush that could conceal Indian raiders were to be avoided as the Indians would use the cover of the brush to their advantage. Camping on the high ground for the ability to survey the terrain was also recommended. Picket guards were stationed at night 200-300 yards away from the camp between the most likely avenue of approach by Indians and the wagons. These guards stayed on low ground when possible to allow Indians to skyline, that is silhouette, themselves against the horizon as they came over the crest of the terrain. In daylight, guards moved to any high terrain for greater observational distance. At night, travelers were confined to the camp. Wagons were loosely circled to help corral the animals and provide a defensible formation against attack. Corralling livestock helped prevent stampedes which might be incidental or provoked as part of a raid. Horses were to be always kept ready to stop a stampede and herd the animals back in lest they get away and scatter over the countryside. Stampedes could be a way to rustle the animals or part of a distraction during an attack. Some horsemen carried their pistols in holsters attached to the saddle which left them handy while mounted, but if they dismounted, they would have to draw the guns before getting off the horse. This left men without their guns if they had to quickly quit the saddle in an attack. The prairie guide’s advice to always keep pistols holstered about the waist is similar to advice in my books to keep guns in the car holstered on your body at all times in case you have to abandon the vehicle in a hurry. Terrorism Indian tactics were not suited for campaign/occupation style warfare as Europeans were accustomed to. Indians used their knowledge of the terrain and living off the land to survive and evade. Raids and ambushes, where the attack was sudden and followed by a withdrawal, were suited to the form of warfare Indians were accustomed to. They could melt back into the wilderness where the settlers were at a disadvantage. Generally Indians fought short wars or engaged in reprisal attacks. The inability to store large quantities of food made supporting a long campaign difficult. Indians who farmed were required to tend their crops so they could not make extended deployments. Militia troops in New England would burn or trample crops and block areas where Indians hunted, fished, or foraged. Out west, Indian logistics were attacked including the infamous buffalo hunts that were intended to deprive the Indians of this resource. Raids on the hunting, fishing, and foraging grounds tended to discourage activity there and displace the Indians, resulting in hunger and famine. Even the choice of settlements on prime hunting, foraging, or gardening land could be weaponized against the natives. Capture of territory in the European sense, where it was held and occupied, was uncommon among the Indians. Sedentary tribes, particularly in the desert, fought over land as water and arable land were scarce resources. Warfare could generally be regarded as competition over limited resources as represented by control of the land. Whites inadvertently or deliberately scared off game. Good farming areas or reliable water sources would be homesteaded and denied that area to the Indians. As a result, Indian raids were intended to force the white man to leave the land. Obviously this was not successful but you can’t blame them for trying. Terroristic attacks with atrocious horrors have universally been a feature of inter-tribal/racial warfare historically. As mentioned above, the worse an attack was, the more likely it was believed to have an influence in causing whites to flee. In many cases, homesteads were abandoned for a time but the whites always came back. Without a large-scale picture of migration trends and the sheer size of the American-European population, Indians can’t be blamed for assuming these methods would work as they did on Mexicans and rival tribes. Comanches, in particular, were notorious for carrying out horrible depredations on their victims. With a poor command structure they were likened to “street gangs.” The most probable motivation was to make warfare so unpleasant that no whites would want to risk an Indian attack and thus avoid their territory. Scalping as mutilation, for instance, could be considered psychological warfare; nobody wants to get scalped. Wounded men and captives were routinely tortured to death. This is why the saying “Save the last bullet for yourself,” became popular. Quarter and mercy was rarely given. Indians treated their victims and captives in the same way that they expected to be treated, and were treated, by other tribes. Like the Japanese during WWII, surrender in the face of overwhelming odds was considered a weakness. Resistance might deter or stop an attack. Even brandishing a firearm in some cases was enough to stop an attack. While part of the reason this worked may have been wise judgement and self-preservation, in other cases Indian warriors respected a courageous fighter. Rape was almost always perpetrated against female victims, white, black, or Hispanic. In some cases, women were raped after being mortally wounded. Rapes occurred in the presence of husbands who were dying or killed shortly thereafter. Girls and children were often kidnapped and taken into concubinage. Infants were regularly beaten to death in front of their mothers. It was savagery to a degree that many tribes disapproved of. Attacks on settlers may also have been retaliation for settler depredations on Indians or for Army attacks (hitting a soft target). Excesses occurred on both sides, usually an over-zealous retaliation for an attack or offense. One side would do something atrocious and the other side might seek to do something worse in revenge. Vengeance was a deep theme among the Indians and a part of tribal warfare from before the arrival of Europeans. Raids Raids on homesteads and wagon trains had multifaced purposes that combined elements of terrorism, to drive off settlers, and result in material gain. Raids upon multiple locations or even feints were possible. Indians might attack one homestead, and as neighbors pursued the Indians or rode to the defense, another group (or the original group circling around), would attack a second, undefended location. Indians stole livestock (cattle and horses) in raids. Entire herds could be stolen and driven into Indian controlled land. Often they were traded locally or driven into Mexico for sale. Animals that weren’t stolen or killed were set loose. Any livestock they could not take with them, like chickens, were slaughtered and they trampled young crops into the ground. Fleeing settlers often set their own animals free so they wouldn’t starve in their pens, and if they returned home, often faced dead crops upon their return. Once the homesteaders were dead, unable to resist, or driven off, Indians would tear the houses apart. Homes were looted of anything valuable or of use to the Indians including food. Vandalism of houses and cabins was common. After looting and vandalizing homes, they were often set on fire. Indians were hard enemies to fight because attack parties could form up from different camps at an initial point or ambush site due to their familiarity with the terrain. European warfare had moved away from this kind of small unit engagements. Likewise, natives could disappear after an action and it would be difficult for white scouts to track them and navigate through often foreign terrain. Being able to break camp or abandon villages while living off the land was an advantage that the plains tribes had over settlers who could not easily afford to abandon their cabins and farms to flee. Poor situational awareness Indians could approach farms and houses undetected mainly because there were too few people living there to keep proper watch. Countless stories, good and bad, start with an Indian showing up at the door. Literally like: “Ma was cooking and suddenly the local chief was standing in the doorway.” In one case, a little girl peeping out the cracks of a schoolhouse saw Indians approaching and was able to escape through a window before the attack began. Alert fatigue is a factor so get more eyes on your homestead to share the burden. Another mistake was knowing Indians were likely to be about and yet going outside, at night, unarmed and without escort. Men would go out to tend the animals, sans gun, only to be sprung on by an Indian. One woman left at dusk to draw some water near a spring that was noted as a prime ambush site due to thick foliage and was shot with an arrow by an Indian hiding in concealment. Ambushes from deep brush was common. In the preceding account, it was known that the brush around the spring was too deep and could hide ambushers, but it was not cleared away. Romans were known for clearing the verges of their famous roads so legions and travelers could pass in relative safety. Had basic military engineering measures to deny the enemy concealment been taken the tragedy may have been averted or at least mitigated. Indians often attacked while settlers were away from the house to separate the victims from their shelter. Any distance that separated one from the home or others could result in ambush; two little girls were killed by Indians when they went to draw water a hundred yards from the house. This could have been prevented had “Pa” checked out the area or escorted the girls. In modern terms armed overwatch with a shooter capable of hitting targets at that distance might have made a difference. Too few men/defenders A recurring theme is that attacks happened when the men weren’t home. Indians knew this and that more than likely the women would be unable to successfully defend the home and attacked. The husband went into a town or trading post and Indians watching the home knew it was unguarded by a man. Or the husband was ambushed by Indians hiding in the brush while cutting wood, traveling, working, etc. With no other men, there was no one to protect the women and children. In many cases, only the man of the house was armed or there was a long gun inside the house that never got to be used. Women did not usually carry pistols but many had access to firearms inside the house. While many women put up a credible defense and there were plenty of heroines, a single woman was seldom a match for multiple Indian warriors. The Indians would also not fear or respect a woman in the same way they would a man. Sexist yes, but history is. Not enough guns was also a problem. Homesteaders were likely to be operating on shoestring budgets and might have one long-gun mainly for hunting. A man with a brace of pistols, a rifle, a shotgun, and a pistol for his wife would have been a rare thing indeed. One small Texas settlement was entered by a band of hostile Indians. There was less than half-a-dozen men and no guns; the town only being saved by the proximity of Texas Rangers whose response caused the Indians to leave. Many fights were turned because of the effective use of firearms by whites. Whites tended to be more accurate shooters, have better weapons, and more ammunition than their native enemies. Indians succeeded at hand-to-hand attacks. This is a lesson in that a better armed and skilled defender can utilize his firepower to overcome the numerical advantage of a more poorly armed or trained enemy. Settler defenses A barricaded home and a defender who was willing to, or did, shoot discouraged some assaults. A shuttered up home might mean someone was armed inside and ready to fire. Some built strong houses with loopholes and protected enclosures for the horses. Iroquois and other Indians surrounded their villages with palisade fencing made of thin, sharpened stakes of wood. Entrances were staggered to deny a straight entry and were barricaded in times of siege. A successful defense was for all the neighbors to “fort up” in the largest and well-protected house if there was time. Men would stand guard outside while the women and children stayed inside the house. If they could not be protected by the house or were driven out, women and children often hid away from the house, such as in tall grass, deep brush, or caves. The Army was tasked with “frontier defense,” which was essentially counter-insurgency warfare. The responses to attacks, raids, and reprisals looked like a horse-borne version of what happened in Rhodesia during the 1970s Bush War. Prairie guides criticized small, widely scattered Army garrisons as too ineffective to provide protection of the frontier. Generally this was the case. Often the only help was from neighbors who joined the fray at the risk of their own lives. In the northeast, settlers formed local militias and small garrisons were present in many communities. Settlements were surrounded by a stockade. Any field work was done under the protection of armed men. Life around 1700 was described as near siege-like. Some eastern colonies required men to carry arms to church. A century and a half later, in the Southwest, “Minuteman” type companies were organized for similar reasons. On the other hand, not everyone cooperated with their neighbors during Indian attacks. French-Canadian settlers had strong ties with native peoples, unlike the British. During Pontiac’s Rebellion, many French refused to offer shelter or aid to British victims who were the primary target of Indian attacks. This article is a part of my new non-fiction book, Rural Home Defense: A cop's guide to protecting your rural home or property during riots, civil war, or SHTF.

|

Author Don ShiftDon Shift is a veteran of the Ventura County Sheriff's Office and avid fan of post-apocalyptic literature and film who has pushed a black and white for a mile or two. He is a student of disasters, history, and current events. Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed