|

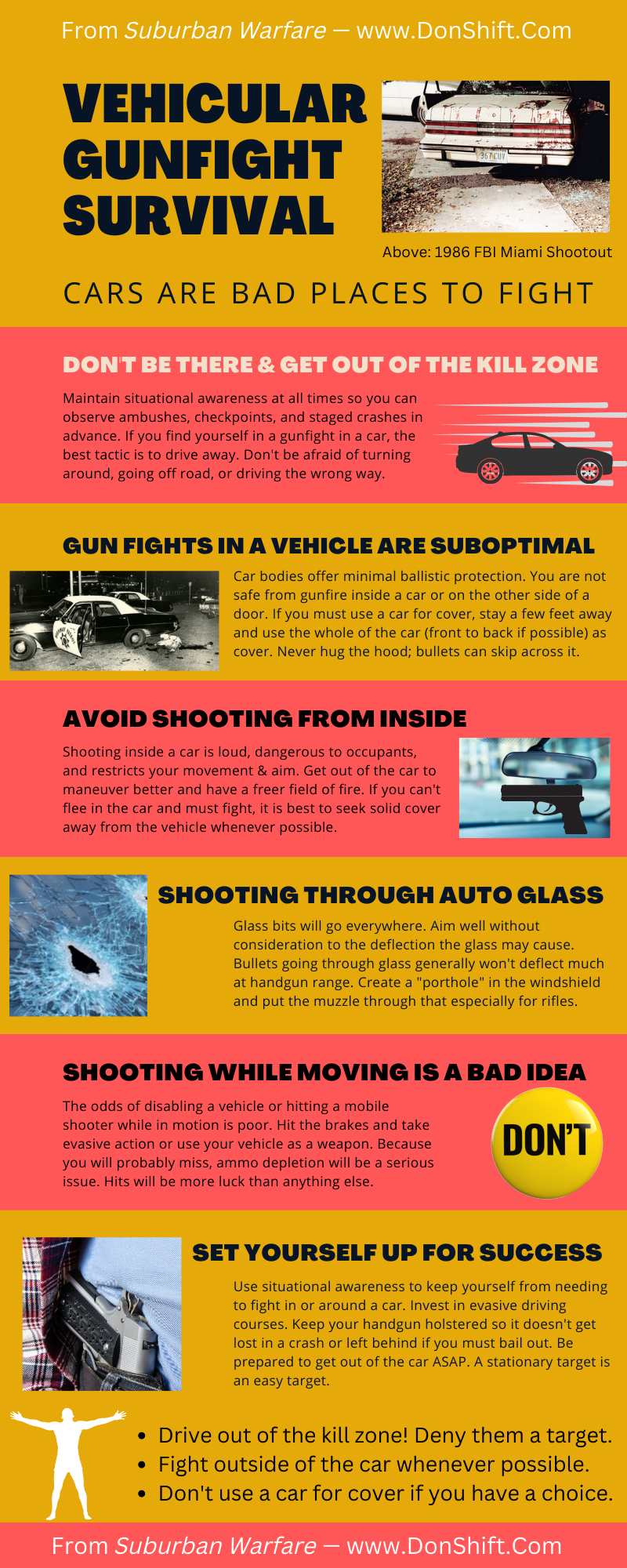

Fighting in and around a car is a bad idea. Situational awareness should be primary so that things never progress to the gun stage on either side. Never put yourself in a position where the fight begins when a criminal or carjacker raises a gun at your side window. Your best defense in a gunfight once things have gone sideways in or near a vehicle is to drive away or use the vehicle itself as a weapon. From there you can assess and fight from a more advantageous position or flee.

Holster your gun on your body so you have it in the same place you would expect it if you fight on foot. This helps you with muscle memory and allows you to retain the gun after a crash or if you have to get out. In 1986, Special Agent John Hanlon lost his gun after it slid off the seat in the collision that began the infamous FBI Miami Shootout. Rifles and long guns should be wedged between the seat and the center console on the inner side of the vehicle. Avoiding obstructions, roadblocks, and bad parking places is key to surviving an ambush. Park away from people and cars, nose facing out. Watch your surroundings and mirrors. Stop in traffic where you can see the rear tires of the car in front of you and try to choose lanes and routes where you aren’t hemmed in by solid barriers. Look far ahead down the roadway and avoid any potential protests/riots, checkpoints/roadblocks, and traffic jams. If attacked, drive the vehicle out of the target area whenever possible. Use the vehicle’s speed, size, and weight to your advantage. Use unpredictable escape routes that may include driving on sidewalks, lawns, or sideswiping other cars if necessary. Even consider slamming on the brakes while driving if a mobile shooter pulls up next to you. Should you be unable to drive away or run away, fight outside the vehicle. It may be appropriate to engage the target while still in the vehicle, before getting out, such as a few shots through the glass at a very close assailant, but avoid treating the vehicle like a little fort. Keep fighting as you exit the vehicle. Move to actual cover if you can. Put the maximum amount of automobile between you and the bad guy. Stay low, crouch, and do not fully stand up when fighting around a vehicle. Do not hug the body panels of the vehicle. Stay back a few feet. Resist the urge to rest your arms and weapon on the hood. This will expose too much of your body and bullets can skip across the hood. Take a knee and get low; shoot through the windows if you have to but don’t stand up and expose yourself through the glass like a naked person in a hotel window who thinks they’re invisible. If you have to shoot inside a car you may suffer irreversible hearing loss as gunshots are magnified by confined spaces. Be mentally prepared for tinnitus and eardrum pain. Dust, gun gases, and bits of glass will be stirred up. If you have occupants, be sure not to shoot them and remember that they could be hit while you choose to fight vs. flee. Shooting through a windshield You can easily shoot through a windshield. There will be some deflection, but at near distances. not enough to matter. The first round through a windshield will likely have the most trouble penetrating; this can be true of any shots that go through undamaged glass. Make your first shot a good one, well placed on the target without consideration to the deflection the glass may cause. Returning fire is more important than trying to dope the glass. Don’t try to adjust your aim based on the bullet holes/impacts on the glass. Pick an aimpoint on the target, keep your aim steady, and fire at that spot. Your intent should be to saturate your target with bullets to get a hit. Even if your shots are less than square range accurate, they may provide a suppressing effect on the bad guy if he isn’t expecting to be shot at. For rifles in particular, if you have the ammo, blow out a large enough area of glass to shoot through the resulting hole. This is called “porting” and it typically takes three to four shots to make a hole large enough to shoot well out of. Put the muzzle up to or through the hole. Shoot out of the hole you made and each bullet will fly to the target true to your aim because it will not contact the glass. (You shouldn’t be shooting from inside if you can help it). Don’t just “aim low” when shooting through the windshield “because the first round will go high.” The first shot (going out) will likely deflect high, but your subsequent shots, unless you are shooting through undamaged glass, will generally not behave the same way. Shots will behave randomly depending on different variables—did the bullet catch the edge of the glass, etc.?—but will land within center of mass if that’s where you’re aiming. The effect windshield glass has on bullets Note: Much of this is academic. Bullet deflection is a problem when precise shots are made, but at close distances, say a few yards, it does not practically matter. Don’t worry about up/down, inside/out deflection. Returning fire, suppressing the threat, and getting out of the car or away from the kill zone is primary. Copper jackets will separate from the lead in a bullet almost always when hitting glass. Jacket fragments may impact the target, passengers, or bystanders. Bullets may be deformed and have reduced performance on target, including keyholing. This is where contact with the glass causes the bullet to yaw in flight impacting the target sideways at lower velocity, producing a hole that looks like a keyhole. Windshield glass is laminated and side/rear window glass is tempered. Windshield glass tends to hang together rather than breaking apart. Side window safety glass breaks into chunks instead of shards. These chunks are difficult to get cut with even on purpose. Windshields are the most resistant to damage and are more likely to spiderweb than shatter. Holes will form and bits will come off, but they almost never will shatter in your lap. Windshields are angled to deflect the wind. The degree of slope varies between vehicles. This slope affects bullets because when the bullet enters, it will make first contact either high or low. That is, the “top”[1] of the bullet will impact the windshield first going out, since the slope makes the high side closer to the “top” of the bullet. Going into a vehicle, the “bottom” of the bullet will make contact with the bottom of the glass first. This is what causes deflection. Shooting out from inside, the bullet will go high because of this effect. Conversely, when shooting into a vehicle through the windshield, the bullet will go down and strike low. This is why some trainers tell students “Aim low when shooting out and aim high when shooting in.” In practical terms this doesn’t matter. Note: this an adaptation from my non-fiction book Suburban Warfare: A cop's guide to surviving a civil war, SHTF, or modern urban combat, available on Amazon. Don Shift is a veteran of the Ventura County (CA) Sheriff’s Office and is a student of emergency response, disasters, and history. He is the author of several post-apocalyptic survival novels about nuclear war, EMP, and the non-fiction Nuclear Survival in the Suburbs, and the Suburban Defense/Warfare guides. His website is www.donshift.com. [1] Top and bottom are relative because a bullet is spinning. Comments are closed.

|

Author Don ShiftDon Shift is a veteran of the Ventura County Sheriff's Office and avid fan of post-apocalyptic literature and film who has pushed a black and white for a mile or two. He is a student of disasters, history, and current events. Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed