|

While California is well-known as being extremely hostile to gun rights, few have any idea of the way things used to be, including that until 1967, California was an unlicensed open carry state. Fewer still know the backstory of how and while open carry became illegal in all but a few instances. California’s real erosion of gun rights did not begin until the late 1980s, but in 1967, during the height of the civil rights movement, another blow was struck against gun rights.

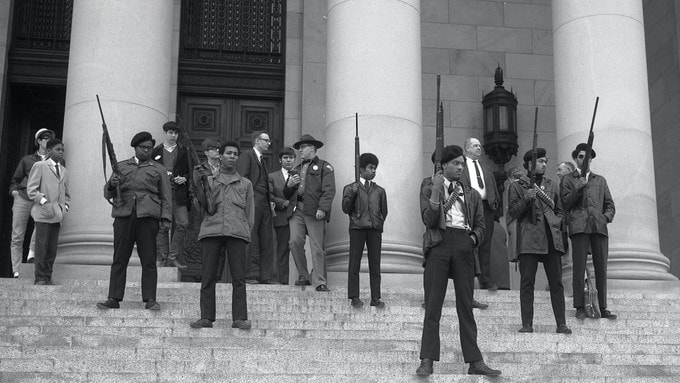

The widely loved Republican, Ronald Reagan, signed the Mulford Act into law, criminalizing the urban carry of a loaded gun in response to actions by the Black Panther Party allegedly in response to civil rights violations of blacks by police. Without a doubt, the methods used by the Panthers were heavy handed and intimidating, possibly unnecessary. I would be remiss to not point out that without their actions, perhaps open carry in California would have survived longer, even to this day. Before I go further, I must explain that the leaders of the Black Panthers were unequivocally bad men—rapists, murderers, and criminals—and they attracted many of the same, but many “decent” folks too, into their ranks. The events here need to be taken into context of fears of communism and leftist violence that had begun to enter the American consciousness as well. Locally, the 1960s in California were as turbulent a time for race relations as anywhere else in the country. California was the number one destination for black families to relocate to. Yet even in the Golden State, unemployment, education problems, and housing discrimination dogged blacks. Tensions between the police and black community simmered in the face of police brutality and discrimination to discount. “Back in those days most non-white people were treated badly, it was hard finding decent housing, very few blacks lived downtown and the schools were still mostly segregated. Red lining by the established Banking policy.”[2] This all erupted in 1965, when the traffic stop of a black man on suspicion drunk driving culminated in the arrests of over 3,000 people. Huey Newton, a black activist, co-founded the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, with Bobby Seale. Just as the Black Panthers developed a reputation of crime and terrorism, Newton was far from perfect. As a juvenile, he was arrested for possession of a firearm, and in college, was sentenced to jail for an assault with a knife. In 1974, Newton was accused of killing an 18 year old woman in Oakland after she called him by a nickname he despised. After returning three years later from an escape to Cuba to avoid prosecution, Panthers attempted to kill a witness, Crystal Gray, against Newton. In the aftermath, a Panther was killed and to cover up the events, another Panther Nelson Malloy was killed. Both actively engaged in ‘copwatching’, the practice of observing police officers on patrol and monitoring their behavior for abuse or misconduct. Newton and Seale’s patrols were not unprecedented. Unarmed police observation patrols had already been formed in the aftermath of the Watts Riot as a response to mistreatment and racism by police against blacks. Participants in the police patrols would listen to police radio on scanners and go to the locations to observe. Note: Much of this is from their own accounts, so the facts may be some opaque. After seeing police brutality first hand, Newton decided to go armed. “Malcolm X and the Panthers described their right to use guns in self-defense in constitutional terms."[3] Elaine Brown, herself a Black Panther leader in the 1970s said: “The position of the Black Panther Party was that black people live in communities occupied by police forces that are armed and dangerous and represent the frontline of forces keeping us oppressed. We did not promote guns, but rather, the right to defend ourselves against a state that was oppressing us—with guns. There were innumerable incidents in which police agents kicked in our doors or shot our brothers and sisters in what we called red-light trials, where the policeman was the judge, the jury and the executioner. We called for an immediate end to this brutality, and advocated for our right to self-defense.”[4] Newton “[...] discovered that California law permitted people to carry loaded guns in public as long as the weapons were not concealed. He studied California gun law inside and out, finding that it was illegal to keep rifles loaded in a moving vehicle and that parolees could carry a rifle but not a handgun. [...] he learned, citizens had the right to observe an officer carrying out his or her duty as long as they stood a reasonable distance away.”[5] The rules of engagement were simple: “When an officer refused to accord [Newton] these rights, he made it clear that he would accept an arrest peacefully but that he would take the officer to court for false arrest. But if an officer attempted to go outside the law and abuse or brutalize him in any way, Newton was armed, as was his legal right, and he made it clear that he could not hesitate to use his weapon in self-defense.”[6] I'm unaware that he ever did this. Newton and Seale’s patrols culminated in the events of one night in 1967 during a copwatching patrol. Eventually growing suspicious, the police pulled over Newton and Seale’s car. On approaching the vehicle, the officer said “What in the hell you n---s doing with those goddam guns? Who in the goddam hell you n---s think you are? Get out of the car with those goddamn guns.”[7] Knowing the stop and commands to be illegal, Newton and Seale decided to fight back. Students from a largely black school were their audience, along with local residents. A scuffle ensued with the officer, who was attempting to grab Seale’s shotgun. Newton fought off the officer. “Now who in hell do you think you are, you big rednecked bastard, you rotten fascist swine, you bigoted racist. You come into my car, trying to brutalize me and take my property away from me.” Responding officers demanded to “see” the firearm, but Newton refused, asserting their legal rights to bear arms. Eventually, the police declined to press the issue and wrote a fix-it ticket for a loose license plate. Blacks who did not submit to police abuse and were armed was distressing to police; heck, anyone carrying a gun around “just because” was unusual. One reporter wrote: “Sure, that right [to openly carry] was good back in the days of the Minutemen, or even the wild west, but supposedly we are modern people with no need to carry guns on our belts.”[8] People didn't feel a need to regularly carry a firearm in the late '60s; the attitude was entirely different and the product of disarmament laws a century old. Next, the Panthers went to San Francisco Airport to provide an armed guard for Betty Shabazz, the widow of Malcom X. Inevitably, this lead to another confrontation with police when the Panthers brought their firearms into the terminal. Officials were concerned about terroristic intimidation by a militant political party. It has to be remembered that at the time, the Black Panthers were the equivalent of Antifa and their protests somewhat like those we saw done by leftists in 2020. Carrying firearms for self-defense was at an all-time low in the country, and open carry in urban areas unusual, so it was no surprise that the behavior what technically legal. "I submit to you that it is preposterous, that in this urban society we have in California, that fishing through the Fish and Game Code and looking at municipal fire ordinances to try and prevent people from carrying weapons around in an excited and hostile atmosphere. [...] no one wants to touch the legitimate hunter, but we've got to protect society from nuts with guns. [...] The Second Amendment [...] doesn't talk about a rag tail tin-soldier army of cannon collectors who are, most of them, are disturbed people anyway."[9] Incidents like this continued, including outside a school in the wake of unrest and anger over the shooting of a black burglary suspect. Denzil Dowell was shot by police after fleeing from a liquor store robbery, when, as the black community at the time believed, surrendered with his hands raised. Rallies were held with armed Panthers, who naturally drew attention, and even a rooftop sentry performing security over-watch. Police reported that these rallies were rather tense and the arms intended to intimidate officers into not interfering. Bloom and Martin sum up the spirit of defiance that so unnerved law enforcement and politicians. “While the police scared many in the community, here was a group of young black men, organized and disciplined, openly displaying guns and speaking their minds.”[10] Newton’s calls for the black community to arm themselves bordered on organizing an insurrection to the political classes. Police weren’t used to having armed people of any race observing their traffic stops and calls for service. Chants like "The Revolution has come, it's time to pick up the gun. Off the pigs!”[11] did not engender non-blacks, who might have supported a pro-gun cause or simply justice and fairness, to the Black Panthers. A month and a half after the incident at the airport, Assemblyman Don Mulford of Piedmont, a Republican, introduced a bill to criminalize urban open carry in California. Mulford was an authoritarian bound to challenge leftist radicals. In 1968, he even went so far as to threaten superior court judges that they would be challenged by well-financed opponents if they were lenient with student protestors.[12]. Until the events of 2020, I would have found all of this horrifying. Mulford’s act had the effect of outlawing the carry of firearms in California. In the World War I period, California adopted its ‘may issue’ concealed weapon permit system, where discretion to issue a permit to carry a concealed weapon lay with sheriffs and police chiefs. A concealed weapon act of 1917 is where California started down its hodgepodge path to gun registration. It was strengthened in 1923 with a combination of three bills in the legislature. The California Concealed Weapon Act of 1923 was and amended again in 1925. Interestingly, legislative intent research mentions that the bill was part of a national push for uniform handgun sale laws, similar to the state-by-state push for private party sale background checks. One news-paper headline speaks of the “possible unconstitutionality of clause provided for in drafting” in the 1923 act. Just who “undesirable persons” are remains undefined beyond the implication that they are ‘criminals’, but as written earlier, California had its own firearm laws intended to disarm blacks, Asians, and Mexicans. Was the Mulford Act explicitly about disarming blacks because of racism? I would say no; it was about depriving the Black Panthers, a radical group, from armed demonstrations. The members just happened to be black. Some would say this is a small distinction but I would argue that given the circumstances of the political climate, the Mulford Act wasn't intended as a racist measure. Others would disagree. “As black assertiveness increased, whites came forward with proposals for tougher gun control. The sponsors did not hide the centrality of race in their concerns. White concerns about gun control for blacks was not new.”[14] Unfortunately, we didn't have an example of white leftist groups demonstrating while armed and also intimidating the police so we'll never have anything to compare it to. In any case, it was the aggressive actions of the Black Panthers while openly carrying that prompted the law; not just because they were black. Again, many would argue a distinction without a difference but I would argue that any latent bias against black people the legislators had a negligible effect. “When Newton found out about the bill, he told Seale, ‘You know what we’re going to do? We’re going to the Capitol.’ Seale was incredulous. ‘The Capitol?’ Newton explained: ‘Mulford’s there, and they’re trying to pass a law against our guns, and we’re going to the Capitol steps.’ Newton’s plan was to take a select group of Panthers ‘loaded down to the gills,’ to send a message to California lawmakers about the group’s opposition to any new gun control.”[15] On May 2, Newton lead a group of 30 Panthers, including 20 armed men, traveled to the state capitol in Sacramento. Instructions were issued not to fire unless fired upon and to always keep weapons pointed in safe direction. One newspaper abbreviated its description of the events to “…an armed band of leather jacketed Negroes stormed into the assembly chamber.” [16] And people think January 6, 2021 at the US Capitol was bad? The Panthers arrived at the capitol and quickly became the center of media attention on their journey to the assembly floor. Sergeant at Arms James Rodney was knocked down by the Panthers when he tried to bar their entrance to the Assembly floor. "I still can hear the panic in the shouting of the presiding officer [...]: 'Sergeant, remove those people immediately.' Nobody was going near those people," said one reporter.[17] Assemblymen took cover. This later became national news, snatching headlines in the major papers from coast to coast. A scuffle ensued with capitol police where one Panther’s gun was snatched by an officer. Tony Beard, a capitol police officer, hustled out both the Panthers and the press who had come in with them. "They broke right through the men guarding the entrance to the chamber. We hustled them out as fast as we could,"[18] said a capitol policeman. An assemblyman wrote: “When I realized that the Black Panthers were armed I was in the rear of the Assembly chamber 10 feet from some of the group. Those gun barrels looked as large as cannons. All the members of the Assembly could have been wiped out in a minute had the fire power been used.” [19] “The action of the state police resembled the Keystone Cops at their worst. The state police, over 140 in total number, are charged with the security of all state buildings and personnel. Only four, however, were available at the time for an emergency and they were not adequate to cope with such an armed group. When they were dispatched from their office on the first floor of the Capitol directly below the Assembly chamber they had to take a circuitous route because the closest elevator is reserved for legislators. [20] Panther Bobby Hutton, chased the officer down to recover his gun and his compatriots followed, clearing the assembly chamber. The Panthers were then quickly swarmed by police and disarmed. “Am I being arrested?” can be heard shouted in the halls. Flanked by a dour state police officer, the Panthers issued a statement condemning the “terror, brutality, murder, and repression of black people.” “[The manifesto] called on Americans, particularly Negroes, ‘to take careful note of the racist California legislature which is now considering legislation aimed at keeping the black people disarmed and powerless. We believe that the black communities of America must rise up as one man to halt the progression of a trend that leads inevitably to their total destruction.’ [21] As the Panthers were ejected from the capitol, they passed a high school group picnicking on the lawn with Governor Ronald Reagan. Reagan was reportedly unnerved by seeing a group of armed men and quickly left for the safety of his office. "Americans don't go around carrying guns with the idea of using them to influence other Americans. This is a ridiculous way to solve problems anyone who would approve of this type of demonstration must be out of his mind,” [22] he said. I think Reagan's statements sum up the thoughts at the time. Intimidation with firearms was looked down upon by society at large and the government. Storming the capitol while armed to cause a ruckus supports the argument that Panthers were engaged in armed intimidation. Invading government buildings while armed looks like an insurrection even if it isn't actually one. The whole point of Newton's stunt was "to send a message." 1960s Black Panther open carry was not about ordinary, daily self-defense carry. The intent to stop police brutality against blacks has to be taken with a grain of salt and seen in light of the other actions of the Panthers. It also wasn't like ordinary black citizens were being disproportionately arrested for open carry while white people were given a free pass. Police followed the Panthers from the capitol, stopping a car containing Sherman Forte at a gas station. Despite Forte’s handgun being openly carried in a hip holster, he was arrested for carrying a concealed weapon (which admittedly was wrong of them). Officers measured shotguns, trying to determine if they could charge the owner with possessing a sawed-off shotgun, by comparing the Panther’s gun to a police riot gun. Others were arrested for having a loaded long gun in a vehicle, a fairly common hunting regulation. The charges were later changed to conspiracy to invade the assembly chambers, a felony. The next day, the Sacramento Bee ran a headline: "Capitol is Invaded," and "State Police Halt Armed Negro Band." Attorney Larry Carlton for the Panthers said in an interview that the Panthers "took extreme measure to protest a pending law. But here again, two wrongs not making a right, the other side is taking extreme measures to punish, which was essentially, I think, a civil rights protest."[23] Ironically, "'Today, the Republicans would be defending the Panthers' right to have guns,' says Democrat Willie Brown, who 40 years ago was an assemblyman and later became Assembly speaker and then San Francisco's mayor."[24] Back at the capitol, within three hours, the assembly criminal procedure committee met “and voted to take Mulford’s legislation under submission.”[25] Mulford doubled down by amending a ban on firearms on state capitol grounds. Mulford said of his bill, “This may become a model for other states to adopt constitutional gun laws to prevent violence but protect the constitutional right to keep arms.”[26] Governor Reagan signed the bill into law. Reagan went on to say that he saw "no reason why on the street today a citizen should be carrying loaded weapons," and that he did not "know of any sportsman who leaves his home with a gun to go out into the field to hunt or for target shooting who carries that gun loaded.” Mulford's bill "would work no hardship on the honest citizen.” He described the Act as: “…a bill intended to put a lid on urban violence by outlawing the carrying of a loaded weapon in a city. ‘I don’t think any true sportsman or gun lover could be against this,’ Reagan said. ‘I don’t think there is anything restrictive in it. I’d be the first to be against any restrictive gun law.’” [27] Ironically, Reagan once used a gun to rescue a woman from a robber[29] and was known to carry a gun at various times, including rumors that he had a gun in his presidential briefcase. In defense of Reagan, the attitude prevalent at the time was that guns were just not needed for the average person in daily society. Our modern concealed carry culture stems from a reaction to the violence of the 1960s-1990s. Despite dramatic, steady increases in all categories of violent crime during the 1960s in California[28], open carry, not widely practiced, was not banned until the Black Panthers became an issue. Even the ostensibly stalwart NRA supported the bill, being thanked for its effort by Mulford himself.[30] In hearings, Mulford denied that his motives were racial, adding that white had also been causing problems. "This has nothing whatsoever to do with the charge that it is pointed at one ethnical group."[31] In a television interview with KPIX denied any latent racism again, though he attributed the need for his bill to the state capitol incident and "when bands of armed people with loaded weapons can move about our streets intimidating and frightening citizens."[32] “This is a reasonable law, once certain exceptions are added that are necessary. It may interest some to know that the often maligned National Rifle Association has been in support of the bill. But there certainly is no justification for carrying a loaded gun on a street, or into a building, whether it be the state capitol or Macy’s. There have to be a few exceptions made, of course. The man going to the bank with the weekend receipts from a huge super market, who carries a gun, wouldn’t have much use for it if it weren’t loaded.”[33] The Mulford Act was a response to political radicalism, not racism. The Black Panthers were not angels, by any means, and were regarded by people at the time as agitators, terrorists, and criminals; in many ways, they were right. Any group of armed minority citizens would have garnered the same reaction; unfortunately, it was a group led by disreputable men that acted. Having the benefit of hindsight and in today’s world of Black Lives Matter and a heated debate on police and their relationship to the black community, it’s easy to see the mythologized Panthers as both victims and heroes in 1967. The Black Panther movement was one that was radical and appealed to more aggressive members of society who felt that non-violent activists like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. wasn’t doing enough. For one who sees the wheels of political justice moving too slowly, shaking things up as the Panthers does has a certain appeal to radical individuals. Yet while in the black and white words of history books Newton and Seale may seem to some like heroes 50 years too early, the Panthers does have any ugly side. The intimidation tactics by the Panthers, especially in California which has had relatively (compared for instance to the South) tame race relations was upsetting. The disenfranchised young men drawn the movement had more than their skin color to frighten the sensitive types. Many had criminal records or engaged in criminal behavior that the police were aware of. “I wish that I could say that there were no abuses by law enforcement going the other direction, but it isn't true. This was a frightening time in America, and the Black Panthers were a scary bunch--not just because they were black men with guns, but because many of them were common criminals--rapists, murderers, armed robbers--before they became Marxist revolutionaries.”[34] Men with records of violence like Newton had didn’t breed confidence that this was just an extreme reaction to discrimination. The fear that the Panthers had more than just armed political demonstrations up their sleeves was real in a time when FBI Director Hoover worried about communist infiltrators. Today, the Panthers may garner more sympathy than in the past because the ugly part of their identity is no longer fresh in the public mind. However, in the years that followed their founding, even members of the press began to repudiate and distance themselves from the tactics, ideology, and acts of the Panthers. New York Times writer Sol Stern admitted that his initial admiration was misplaced. "Within a few years, I understood that I should have described Newton and his cadres as psychopathic criminals, not social reformers. By now, a torrent of articles and books, many written by former sympathizers, has voluminously documented the Panther reign of murder and larceny within their own community. So much so that no one but a left wing crank could still believe in the Panther myth of dedicated young blacks 'serving the people' while heroically defending themselves against unprovoked attacks by the racist police."[35] In light of the Panthers’ and Newtons’ reputation, it is little wonder why they were seen as such an urgent threat. The death of open carry in California is one without any heroes, but villains aplenty. In the end, disarmed Californians were the victim. There are no known incidents of whites—or any other race—engaging in a similar protest pre-1967 in California. Additionally, there was never any major hubbub over the open carry of firearms in California. Truth be told, it was a rarer practice than in open carry states today, likely limited to a few individuals and sportsmen simply transporting their weapons. Carrying loaded firearms (handguns) in vehicles was more of a self-defense concern, which prompted a 1968 bill to undo that specific prohibition of the Mulford Act[36]. Many Californians surely supported the bill. Posing the problem as ‘armed radicals, invading the state capitol, intimidating police officers, and blocking off streets with armed guerillas, including snipers, to rally supporters’ who wouldn’t support the law? Seeing law and order turned upside down by black, communist radicals surely upset many. Not enough support for gun rights existed that groups like the NRA, mostly a recreational shooter’s organization then, saw the problem as a social order issue, not one of civil rights of the Second Amendment variety. None seemed to think about the repercussions that banning open carry would have on the California public at large. With concealed carry essentially illegal, the Mulford Act deprived all Californians of the right to effective self-defense with a loaded firearm. Unloaded firearms were not prohibited by the bill as no one expected that in later years activists would begin to carry unloaded handguns. With the typical lack of knowledge about the critical elements of laws, it is a virtual certainty that citizens were totally discouraged from carrying a firearm, even unloaded, for self-defense. As covered elsewhere, the national resurgence of open carry in the late 2000s led to unloaded open carry being practiced in California. This lead to a number of interactions with police of varying degree and outcome. In response to predominately white and Hispanic open carriers openly carrying unloaded handguns (no magazine in the weapon, often on the other hip), Gov. Jerry Brown signed a bill banning the practice in 2011.[39] In the 21st century, California's open carry panic was over anti-gun hysterics and the panic that gun-rights activists found a "loophole." Unloaded open carry got banned precisely because people were taking advantage of the only way the majority of Californians could legally carry a gun in public. The tactics of the open carry movement are something else, but in modern times we see that the ban centered around the gun and not the race of the carriers. To summarize, I don't believe that the Mulford Act was a racist measure. Racism may have been implied behind it due to general attitudes at the time, but to smear it as a racist gun control law just because the Black Panthers were black is disingenuous and superficial. We shouldn't be pushing a racist narrative to the law simply because it appeals to a demographic that we want to support Second Amendment activism. [1] Williams, Edward Wycoff. Fear of a Black Gun Owner. The Root. Jan. 23, 2013. [2][2] http://www.itsabouttimebpp.com/chapter_history/pdf/sacramento/sacramento_chapter_of_the_black_panther.pdf [3] Winkler, Adam. Gunfight: The Battle Over the Right to Bear Arms in America. 2011. [4] McDowell, Leila. "Ex-Black Panther Head on Gun Control, Obama." The Root. Feb. 18, 2013. [5] Bloom, Joshua and Martin, Waldo E. Jr. Black Against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party. University of California Press. 1993. Ch. 1. [6] Ibid. Ch. 3. [7] Ibid. Ch. 2. [8] “Gun Law Needed.” Corsair. Vol. 52, No. 16. Dec. 17, 1980 p. 2 [9] TV interview. Unknown official. KRON. Circa 1960s. [10] Bloom and Martin, Ch. 2. [11] https://vtspecialcollections.wordpress.com/2013/02/21/power-to-the-people-the-revolutionary-literature-of-the-black-panthers/ [12] Bloom and Martin, Ch. 13 [13] Report of the California Crime Commission. 1929. [14] Beito, David T. and Beito, Linda Royster. Black Maverick: T. R. M. Howard’s Fight for Civil Rights and Economic Power. University of Illinois Press. 2009. [15] Durning, Joseph. "The Secret History of Guns". The Atlantic. Sept. 2011. [16] Capps, Edwin S. (Capitol News Service). “Black Panther Incident Stresses Gun-law Need.” Palos Verdes Peninsula News. May 10, 1967. p. 29 [17] Skelton, George. Los Angeles Times. May 3, 2007. [18] Salzman, Ed. "Armed Foray in Assembly Stirs Wrath." Oakland Tribune. May 3, 1967. [19] Desert Sun. Aug. 23, 1968 p. 4 [20] Desert Sun. Aug. 23, 1968 p. 4 [21] “Reagan Orders Check Of Office Security.” Desert Sun. May 3, 1967 p. 1 [22] Salzman, Ed. "Armed Foray in Assembly Stirs Wrath." Oakland Tribune. May 3, 1967. [23] TV interview. Larry Carlton. KPIX. May 3, 1967. [24] Skelton, George. Los Angeles Times. May 3, 2007. [25] “Reagan Orders Check Of Office Security.” Desert Sun. May 3, 1967 p. 1 [26] United Press International. “Governor Signs Gun Measure.” Desert Sun. July 28, 1967. p. 1 [27] United Press International. “Governor Signs Gun Measure.” Desert Sun. July 28, 1967. p. 1 [28] http://www.disastercenter.com/crime/cacrime.htm [29] “Reagan Was Hero To Iowa Woman, Nursing Student Rescued From Mugger By Reagan”. KCCI. Jun. 7, 2004. http://www.kcci.com/Reagan-Was-Hero-To-Iowa-Woman/7308028 [30] http://cloudfront-assets.reason.com/assets/db/14030325867418.pdf [31] Salzman, Ed. "Armed Foray in Assembly Stirs Wrath." Oakland Tribune. May 3, 1967. [32] TV interview. KPIX. May 3, 1967. SFSU digital collection. [33] Capps, Edwin S. (Capitol News Service). “Black Panther Incident Stresses Gun-law Need.” Palos Verdes Peninsula News. May 10, 1967. p. 29 [34] http://www.claytoncramer.com/popular/WashingtonOpenCarryBan.html [35] http://www.city-journal.org/html/ah-those-black-panthers-how-beautiful-10014.html [36] Desert Sun. March 8, 1968. p. 12 [37] RCW 9.41.270 [38] House Bill 123. http://leg.wa.gov/CodeReviser/documents/sessionlaw/1969pam1.pdf [39] Assembly Bill 144 |

AuthorNote: this an adaptation from my non-fiction book Suburban Warfare: A cop's guide to surviving a civil war, SHTF, or modern urban combat, available on Amazon. Archives

December 2023

|

The information herein does not constitute legal advice and should never be used without first consulting with an attorney or other professional experts. No endorsement of any official or agency is implied. If you think this is in any way official VCSO business; you're nuts. The author is providing this content on an “as is” basis and makes no representations or warranties of any kind with respect to this content. The author disclaims all such representations and warranties. In addition, the author assumes no responsibility for errors, inaccuracies, omissions, or any other inconsistencies herein. The content is of an editorial nature and for informational purposes only. Your use of the information is at your own risk. The author hereby disclaims any liability to any party for any loss, damage, or disruption through use of the information. Copyright 2023. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. Donut icons created by Freepik - Flaticon